The “chic” emphasis of late on how much rich people fucking blow (see also: The White Lotus, Hellraiser, Bodies Bodies Bodies) has been crystallized at perhaps its finest in Ruben Östlund’s latest film, Triangle of Sadness (a lovely shape-oriented title to follow up The Square). Wasting no time in getting to the point, Östlund sets the stage in the world of fashion. Specifically, male modeling. Wherein, for once, it’s the men who are underpaid and harassed (by the largely gay male population that dominates this facet of the industry). Including Carl (Harris Dickinson), a rather standard-issue vacuous model who stands against the wall and subjects himself to a reporter making a mockery of high fashion’s elitism by telling Carl to pretend he’s modeling for an expensive brand by looking as serious as possible a.k.a. looking down on the consumer (which, yes, every ad campaign from a luxury brand seeks to do with its stoic, often famous models).

Carl appears like a fish out of water as the casting directors tell him things such as, to paraphrase, “Models are expected to have a personality now” (a load of bullshit designed to make the art of being thin and hot seem more “meaningful” than it actually is). Something Madonna’s daughter, Lola, knows all about. In addition to nepotism being a key to one’s success in the business (see also: Kaia Gerber). Carl, in contrast, comes across like he never left the 90s school of “thought” on modeling as he walks vacantly up and down the room, eventually resulting in him being told to get rid of that “triangle of sadness” he’s sporting… better known as the furrowing of one’s brow that makes such a formation at the top of their nose. So yeah, not the best audition (yet probably not the worst either).

Later on, it doesn’t look as though things are going much better for Carl in his personal life as he dines with fellow model and influencer, Yaya (Charlbi Dean, who tragically died just before Triangle of Sadness’ international release). As she stares at her phone (the scene many a dinner companion is familiar with), she absently thanks him for getting the check. To which he soon spotlights (after Yaya pries it out of him) that she never leaves him much choice with regard to paying the bill—even though she makes more money than he does. Yaya balks at his complaining as the argument continues in the car on the way to the hotel and then at the hotel as Carl insists that he wants them to be like best friends, prompting Yaya to reply that she doesn’t want to fuck her best friend (though we all know Joey Potter did). And also: talking about money isn’t “sexy”—which is part of why “poor people” are so grotesque to the rich, who never have to discuss or question the spending of every little nickel and dime.

In irritation, Carl says what he means by “best friends” is that he wants them to be like equals. Yaya, perhaps not so naïve about gender roles, regardless of the century, later confesses to him in the hotel (after he’s derided under his breath that women of the present are “bullshit feminists”) very bluntly: she needs to be with a man who can take care of her. Because what if, say, she gets pregnant and can’t model anymore? Carl admits she doesn’t seem like the type who could work in a supermarket. As it also becomes clear that both are only in this “relationship” to grow their social media following, Carl vows to make Yaya fall in love with him for real—none of this “trophy [wife] bullshit.” With the establishment of looks as about the only way to secure money (“beauty as currency,” as Östlund refers to it) if you’re not born into it already, Östlund takes us into a new phase of the movie.

Divided into three parts, “Carl & Yaya” ends so that we might enter “The Yacht” portion of the film. And oh, how pronounced class is during this second act, with the truth about Yaya and Carl managing to get onto this yacht filled with primarily middle-aged and elderly ilk being that Yaya used her “hotness” to assure plenty of pic posting to make the cruise look as (literally) attractive as possible. In short, to mislead people into believing that anyone youthful and beautiful actually goes on these types of excursions when, in fact, it’s mostly people such as Dimitry (Zlatko Burić), an aged Russian oligarch who likes to quip, “I sell shit” in reference to being the King of Fertilizer throughout Eastern Europe and beyond. In point of fact, any rich person can describe how they made their fortune as, “I sell shit.” A lot of fucking useless bric-a-brac no one really needs and that daily decimates the environment. The same goes for Winston (Oliver Ford Davies) and Clementine (Amanda Walker), an old British couple who informs Carl and Yaya that they finagled their wealth by “defending democracy”—better known as arms dealing.

While someone as gross as Dimitry has managed to secure companionship in Vera (Sunnyi Melles, a real-life princess of Wittgenstein), as well as a daughter (?), Ludmilla (Carolina Gynning), who comes off more like a mistress (think: the Ivanka to Dimitry’s Donald), app creator/tech “titan” Jarmo (Henrik Dorsin) is too socially awkward/incel-like to have much game with women. And what use is money to a man if it can’t be used to treat “the ladies” more freely as objects? This is why, when Yaya and Vera, who have taken a shine to one another in their social media-obsessed affinity, offer to pose with Jarmo to make another woman who didn’t come on the cruise with him jealous, he tells them how much it means to him. And then offers to buy them some expensive watches. Costly, shiny things being the only way to show gratitude among the rich and rich-coveting.

Behind the scenes of it all is Paula (Vicki Berlin), the head of staff doing her best to keep morale up by assuring her crew members that they might get a very big tip at the end of it all…so long as they agree to pander to every absurd demand from the guests. This prompts the crew to start chanting excitedly (and crudely), “Money, money, money, money!” reminding one of Molly Shannon as Kitty Patton chanting, “It’s all about the money, money, money” in The White Lotus. What it all proves is that even (and especially) the non-rich are motivated by money, despite it being the very thing that renders them so powerless in this life. By playing into its worship, the lower classes only end up further enslaving themselves to the rich. Meanwhile, even further down below, Abigail (Dolly de Leon), “Head of the Toilets,” is miffed by the bizarre shaking and rattling of the “middle-class” crew up above. In this particular scene, there is something very Parasite-esque about the filming, designed to accent that beneath every “low” class is still an even lower one doing far more grunt (read: bitch) work.

What’s more, in every instance of a rich motherfucker presented, none of these people actually “make” or “do” anything tangible to secure their bag. Yet somehow what they “do” is considered more “valuable” (based on bank account) in our society than those who actually buttress the entire operation of day-to-day existence. And this is where “The Island” segment of Triangle of Sadness comes in—to remind the rich assholes who end up stranded on it that they ain’t shit without “the help.”

Having arrived to this point through a series of “unfortunate” (a.k.a. entirely the fault of the wealthy’s whims in demanding that all the crew members take a swim for thirty minutes) events, the main escalating factor is the improper temperature of shellfish ultimately served at the captain’s dinner. The captain being a reclusive and drunken man named Thomas (Woody Harrelson) that Paula, with the help of Chief Officer Darius (Arvin Kananian), finally manages to coerce into coming out for this accursed obligation. Until this rare appearance, we only ever hear his voice from behind the door, just like Paula. But it’s clear Harrelson took the role so that he could shine during a very “this is the Titanic sinking” part of the movie, during which he goes mano a mano with Dimitry about capitalism versus socialism (Thomas being an American socialist and Dimitry being a Russian capitalist) by quoting a series of “thinkers” to one another and their stances on the subjects.

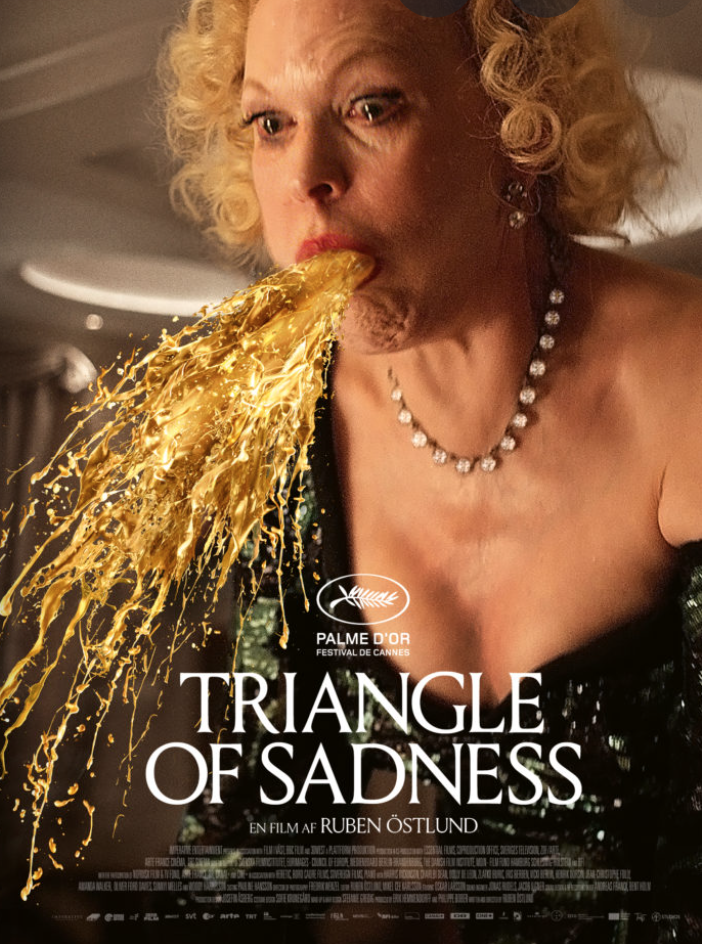

The idea that rich people truly believe their shit (and vomit) doesn’t stink quickly becomes manifest during the now iconic segment featuring the non-stop bodily “elimination” processes of the uber-affluent (most especially Vera). Still subject, in the end, to the limitations of their own bodies, no matter how much money they have. So sure, maybe “we’re all equal” at the basest level of “being human,” with this “we’re all equal” lie serving as a running phrase—whether written or spoken—throughout the film. Yet, obviously, it’s something the rich only wish to tell themselves as a means to shirk any sense of guilt about what they have (which, again, is why Vera demands that the entire crew takes a swim break). More precisely, the excesses of what they have.

This is a topic that arises heavily during the “quote competition” between Dimitry and Thomas as the boat devolves into total shit-and-vomit chaos. With Thomas reciting such Marx aphorisms as, “The last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope.” Dimitry ripostes with quotes from the likes of Reagan and Thatcher, the latter having once said, “The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money.” As their warring ideologies play out in “good fun,” the passengers endure their own added element to the bodily fluid-filled hellscape in that most of the volleying is broadcast over the intercom.

As the absurdity of it all mounts, the only thing that was still missing was the arrival of pirates onto the scene. Which is how we come to find a select few of the passengers washed up on the aforementioned island. Where Abigail, the so-called lowest of the low out in the “real world” is suddenly Top Dog (or “Captain,” as she calls herself) in this setting. All because she has basic skills for survival that the rich never had to learn in their position of “power” that has now rendered them powerless. In spite of this reversal of circumstances, it’s apparent that Östlund wants to ask the question: is life without the social constructs of “civilization” any less savage? Not really, as Lord of the Flies already taught many high school students long ago. Indeed, in the end, Carl himself is the “bullshit feminist.” He doesn’t care about equality, he just wants his fucking meals fed to him in exchange for offering up his body. Beauty as currency, even here.

With regard to managing to keep the tone comedic amid the brutal subject matter/mirror held up to the audience, Östlund invoked the names of two very specific filmmakers past who also had the same ability as he commented, “I felt I wanted to make movies like [Luis] Buñuel and Lina Wertmüller in the 70s, where there was no contradiction between being entertaining and dealing with something that they thought was important.” And, now more than ever, nothing is more important than keeping the spotlight on the ceaselessly-increasing divide between the haves and have-nots. Particularly as we embark upon a new era of climate change apocalypse.

And, speaking of that, a tongue-in-cheek moment that addresses this very inevitability arrives during a fashion show that projects on a backdrop screen something to the effect of, “We’re entering an entirely new climate…” The viewer is briefly inclined to believe this is another attempt at greenwashing until the phrase concludes, “…in fashion.” In other words, the rich really don’t give a fuck if the world is burning so long as they can still “make” (i.e., siphon) money during the decline.

Despite Triangle of Sadness coming across as endlessly “cynical” (that word used to write people off who speak the truth), Östlund portrays all of this precisely because he still has some faint glimmer of hope for humanity. If he didn’t, he likely wouldn’t explore these “uncomfortable” topics in his films at all. And as for being deemed another “guilt-racked liberal” by wealthy conservatives that might happen upon the movie, Östlund remarked, “To call someone a hypocrite, it comes very often from the right-wing perspective: ‘You shouldn’t talk about a better society, because you’re a hypocrite. Look at yourself.’ We can’t separate ourselves from the culture that we live in.” And the culture we live in is the very symptom of our sickness—vomit and all. To which government and big business at large has said, “Lick it up, baby, lick it up.”

[…] between The Squid and the Whale and Triangle of Sadness, Armageddon Time is in the middle of the Venn diagram. With the former still being among the […]

[…] between The Squid and the Whale and Triangle of Sadness, Armageddon Time is in the middle of the Venn diagram. With the former still being among the […]