For a long time, the push toward “modernization” (a thin veneer to layer over what remains barbarism) seemed designed to make anyone who still clung to nature come across as some kind of freak and/or simpleton. Kya “Marsh Girl” Clark falls under this categorization easily in her small, judgmental town of Barkley Cove. Although fictional, it’s something one can find in New Orleans and Houma, both milieus playing the character of North Carolina and its marshlands in the film. To that end, there is something decidedly Dawson’s Creek (itself filmed in picturesque locations throughout the real NC, including Wilmington, Wrightsville Beach, Carolina Beach Southport and Kure Beach) about the aesthetic.

Not to mention the love triangle that eventually brews. And yes, love triangles seem to have been resuscitated again in pop culture, with yet another screen adaptation from a book, The Summer I Turned Pretty, becoming quite “the thing” this year. It, too, featuring many a Taylor Swift song, while Where the Crawdads Sing opts for just the one original composition made expressly for it, “Carolina.” In both cases, however, Swift’s presence as a beacon of “thoughtful white people shit” as it relates to tortured and jilted love reminds one that her work would’ve fit quite nicely in many episodes of Dawson’s Creek. The post-Shakespearean OG of cultivating love triangles. In truth, Kya (whose real name is Catherine Danielle) reminds the seasoned viewer of Joey Potter (Katie Holmes) in many regards. Her deadbeat, shady father, her “ragamuffin” ways. Being a girl from the “wrong” side of town and all that. Of course, Kya takes it one step beyond, living entirely apart from Barkley Cove in the wild.

For some part of her childhood, she lives there with her mother and father, as well as her sisters and brothers, Missy, Murph, Mandy and Jodie. But her patriarch’s drunken irascibility (making him highly prone to physical abuse) eventually sends everyone packing, with Kya’s mother being the first to leave in a battered state and dissociated trance. The image of her mother’s back as she walks away without turning around when Kya screams out for her is a scar that will linger for her entire life, setting the precedent for her mistrust in people who claim to care about her. She knows somewhere deep down that they will always leave. This is a revelation that comes yet again when Tate (Taylor John Smith) gets close to her (after previously encountering her in the marsh during their childhood), only to end up breaking his promise to return after going away to college.

It’s later on that we understand Tate’s reasoning. How stepping out into the “real” world so fully forces him to acknowledge that Kya could never live in it. She’s too free and wild to adhere to the norms of “civilized” society, which itself feigns offering “freedom”—a claim that’s particularly phony baloney in the U.S. But Tate knows Kya well enough by now to comprehend that she possesses a form of liberation and self-reliance that would be at total odds with life outside the marsh. He suddenly feels as though he has to choose between her and a future where he can pursue his own dreams—which, unfortunately, require him to leave the confines Kya has firmly established for herself.

It is then that Chase Andrews (Harris Dickinson) comes along to employ what Kya in the book would call the “sneaky fucker” strategy. A mating ritual performed by male seals on the outside of a harem looking to enter the fold (no pun intended) while the dominant “owner” of the harem isn’t aware. To this point, the parallels between the savagery of Nature and how “civilized” humans themselves behave are a running theme throughout Lucy Alibar’s script, deftly brought to life by director Olivia Newman through a nonstop barrage of breathtaking scenes from nature (indeed, you might call Where the Crawdads Sing an Earth sign’s wet dream). But Kya knows it isn’t all beauty and idyllic snapshots. There are dark sides to survival, even if she repackages that thought to her eventual book publisher as the notion that animals have no choice but to come up with creative ways to “endure.” Just as she has over the years, left to fend for herself by everyone who was supposed to care about and for her.

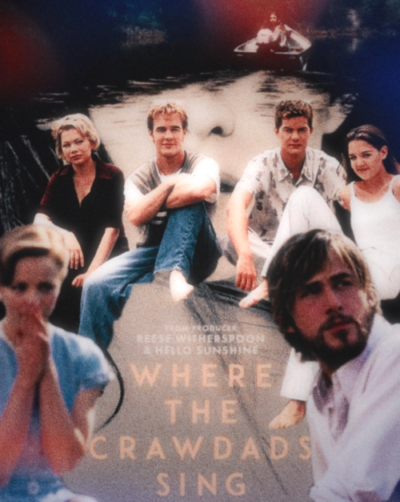

Tate’s misunderstood absence does, indeed, feel like that period of time in The Notebook when Noah (Ryan Gosling) and Allie (Rachel McAdams) were separated. What’s more, it also takes place in a Carolina tableau: Seabrook (though that was actually Mount Pleasant, SC on film, with Nicholas Sparks choosing New Bern, NC as the setting in the book). Noah and Allie’s own palpable divide is one of class—which, in its way, still pertains to a matter of “good breeding” as it does with Kya and Tate, and later, Kya and Chase. More so in the latter permutation as Tate actually knows something about hard labor. It’s all part of the classic love triangle that finds two men of different “stations” in life competing for the same woman. Even Reese Witherspoon (heavily involved in the film via Hello Sunshine) knows something about a good Southern love triangle (see: Sweet Home Alabama). And any of them worth their weight in high drama will make one of the men “lower-class.” As was the case with Pacey Witter (Joshua Jackson) in Dawson’s Creek, which, in the end, seemed to make him more relatable to Joey than Dawson.

Both Joey and Kya aren’t quick to forgive men who betray them, no matter how much they claim to love her. For Joey, it was Dawson putting her in the position of having to turn her father in for drug dealing (again). For Kya, it’s Tate’s seemingly callous abandonment. His reneging on the promise to return. She only wishes that Chase would never come back after realizing he’s been engaged to a more “appropriate” girl the entire time they’ve been together. And yet, despite Chase being the one to betray and cause harm, he has the gall to act affronted by Kya’s rejection. As her father taught her, “These men had to have the last punch.” Luckily, Kya is trained in all the ways of Mamma Natura, and knows that, sometimes, for prey to survive (“endure,” as she calls it), they must kill their predator. By any creative means necessary.

To that end, the foreshadowing and symbolism throughout the film is often heavy-handed, but perhaps only a reflection of the source material, with author Delia Owens writing things like, “Female insects, Kya thought, know how to deal with their lovers” in reference to female fireflies and praying mantises, the former capable of luring males of another species to their death and the latter, as we all know, ultimately inclined to kill her “mate” mid-fuck. Kya, at the very least, is generous enough to let her mate finish his climax. That’s more than most men even deserve.