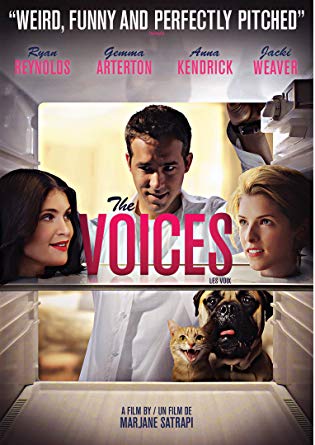

Is it challenging to make a schizophrenic serial killer come across as endearing? Not for Ryan Reynolds interpreting Michael R. Perry’s deftly paced script for The Voices, directed by Marjane Satrapi (of Persepolis fame). In the role of Jerry, Reynolds is given the opportunity to combine his winsome good looks (à la Ted Bundy) with his natural knack for comedy. And while perhaps most people don’t imagine schizophrenics to be able to engage in the stark raving normalcy of owning a cat and a dog, Jerry does just that.

In point of fact, his cat, Mr. Whiskers, and dog, Bosco, are his best friends thanks to his ability to imbue them with animated conversation as a result of his illness. An illness that his own mother used to attribute to being able to “talk with the angels.” Something his court-mandated therapist, Dr. Warren (Jacki Weaver), reminds him of when she asks him if he’s taking his medication regularly and, more to the point, if he’s been hearing any voices. Careful to sidestep her question without “technically” lying, Jerry returns, “When there’s someone talking to me.”

In between having intense conversations with his pets (mainly the more cerebral Mr. Whiskers) and going to therapy, Jerry works at a bathtub factory where he is ostensibly the laughingstock when his back is turned. Especially by his own crush, Fiona (Gemma Arterton) in payroll. Yet despite Mr. Whiskers’ warnings to stand down from even bothering with her, he asks her out. After being stood up and then eventually “accidentally” stabbing her, the cat asks, “Did you fuck the bitch?” Jerry balks, “I don’t have to answer that.” Seeing right through him (because he is him), the cat goads, “And you’ll never fuck her either, because you disgust her. She’s from England, Jerry. You’re out your league. She drinks tea in carriages and fucks men named Nigel. Not Jerry Hickfang.” Ah how it all so effortlessly applies to the current state of affairs with that inexplicable sense of British superiority stemming from centuries of imperialism now manifesting into Brexit.

And though Jerry is often endlessly vexed by the devilish pressures of Mr. Whiskers, his obvious “bad conscience,” now and again he has Bosco to chime in with the doltishly delivered assurance that Jerry is a “good boy.” Yet even Bosco starts having trouble believing as much as the bodies continue to pile up–momentarily paused during a blip when the disembodied head of Fiona tells him he should take his meds. Mr. Whiskers, ever the pragmatist, cautions, “Take those drugs and you will enter a bleak and lonely world, Jerry.” Those words never seemed to ring truer when the effects of the meds kick in and Jerry suddenly sees his world as it truly is: filled with blood, corpses and grayness. Worse still, he’s lost two of his best friends. He’s quick to return to his old tried and true method of simply abstaining from them, essentially adhering to the voice of his mother echoing, “Stay with me in my world.” Ergo Mr. Whiskers’ world as well–the pitch-perfect archetype of what every cat is not so secretly thinking: “Where the fuck’s my food, fuckface?” Which is precisely what he demands upon Jerry’s late arrival one morning after spending the night with another (still living) coworker from payroll, Lisa (Anna Kendrick, always typecast as the girl who falls for the damaged goods). Little concern, in fact, is given toward the knowledge that Jerry is about to end up killing again. After all, as Mr. Whiskers puts it (in the Irish lilt delivered by Reynolds himself, who also voices the other animals–alive or not–in the narrative), “There’s no shame in it. It’s instinct. The only time I felt truly alive is when I’m killing.”

As a result of the cat’s urgings, Jerry does his best to place blame on him for “making him do it,” as it were, a copout that neither Bosco nor Fiona’s severed head agree with. Still, Mr. Whiskers offers to play “devil’s advo-cat” and go along with Jerry blaming it all on him for a moment by remarking, “Let’s say it was me…but, you know that I’m a talking cat. There’s no such thing. Everything I say is really you.” With this terse but logically reasoned out argument, Jerry has to admit that the cat (a.k.a. an aspect of himself) is right. With this revelation comes the question that Jerry hasn’t quite reckoned with yet in terms of arriving at an answer: “Well, is it something that you are, like being brown-eyed or right-handed, or is it something that you choose, like being an accountant?”

Before Jerry can fully grapple with the idea that it might be the former, things escalate to a certain point of no return (just as they did when he was a child, and he developed his rap for insanity in the first place) and the decision is never quite made–if it really ever could be. Yet thanks to the gentle and occasionally nudging presence of Bosco, all slobbering with good-naturedness, a part of the audience wants to believe that there is legitimate decency to our unlikely (then again not that unlikely as he is a white male) serial killer. For it is the ultimately harsh wisdom of the dog that Jerry chooses to heed. Mr. Whiskers, well, he’ll always land on his feet, find another human fuckface to feed him.