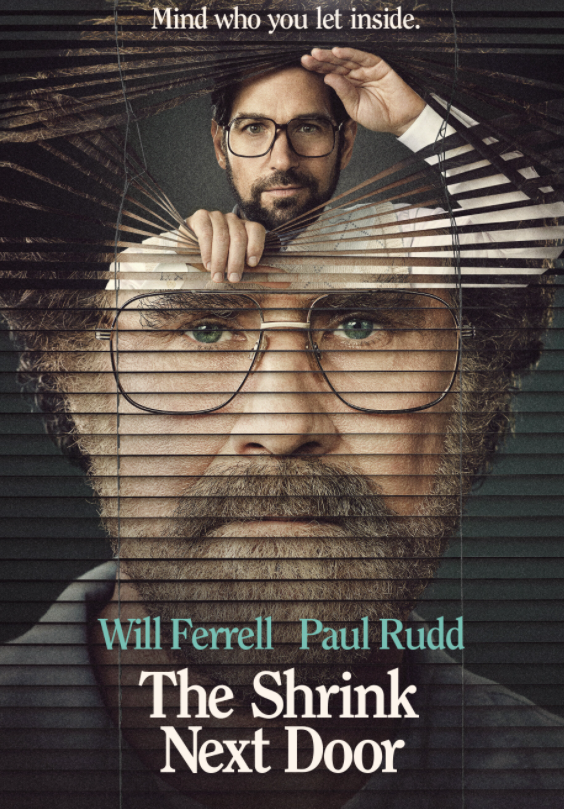

Marty Markowitz (Will Ferrell) is not the type of person we’re supposed to feel bad for. Throughout the duration of The Shrink Next Door, an adaptation of the podcast of the same name, he shows himself again and again to be a glutton for the pain inflicted upon him by this specific form (art, really) of manipulation. Not only that, but he’s rich. And we’re never supposed to fall for the trap of feeling bad for rich people. Isaac Herschkopf (Paul Rudd) certainly didn’t. Yet something about Marty’s innocence—his wholesome, trusting nature—makes us cringe and squirm in our seat as we watch him get taken advantage of repeatedly by Dr. Herschkopf, the very shrink he’s entrusting to “help” him.

Although in real life (for, yes, the story is, quelle surprise, based on true events), Marty was referred to Herschkopf by his rabbi, in the limited series, it is his sister, Phyllis (the inimitable Kathryn Hahn) who ends up sending him into the wolves’ den despite only wanting to give him a mental boost. She urges him, per the recommendation she gets from the rabbi, to make an appointment with this “good doctor.” Finally agreeing to, Marty doesn’t intuit from the outset that Isaac a.k.a. Ike isn’t exactly an “orthodox” practitioner of therapy. His first clue should have been Ike taking him out of the office only to end up at the frame shop where Ike can “coincidentally” retrieve some photos he got framed of himself and a certain “celebrity”: Jackie Stallone. “What? You don’t recognize Jackie Stallone? Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling?” (that’s sort of his whole thing in life: having his picture taken with celebrities, however middling—itself a symptom of a larger condition called Please Love Me and Think That I’m Important).

When Ike mentions that they’ve “technically” gone over their session time, and that he also “happened to” leave his wallet behind, Marty is easily convinced of paying him for a full two hours in cash so Ike can, in turn, pay for his wares. It’s a subtle yet extremely overt maneuver on Ike’s part, and one that even the frame guy can see, but likely doesn’t feel it’s his place to point out—plus, he wants to get paid himself. And in this way, it’s almost as though Marty passed, with flying colors, Ike’s test of determining: 1) how effortlessly duped is this simp? and 2) how much can I milk this guy for? As it would turn out, Ike would extract 3.2 million dollars “over the course of twenty-seven years,” as a title card at the end of the final episode, “The Verdict,” tells us. That probably doesn’t include the calculation of making Marty’s Hamptons house entirely his own (while Marty stayed in the guest house) so that he could throw his little fêtes to impress celebrity clients and other assorted “bon vivants.” Meanwhile, most of the attendees over the years assumed Marty was the groundskeeper. There’s even an episode called “The Party” during which Marty mentions he is the owner of the house to someone “important,” later causing Ike to rebuke him. Any “normal” person would fight back, tell Ike to remember his place in the so-called friendship and that he’s just a guest taking advantage of Marty’s “kind” soul. Though, ultimately, his is a lonely soul. Those are the easiest to prey upon, especially for shysters like “Dr.” Herschkopf. And Marty is an impuissant sucker if ever there was one.

Insulated his whole life not only by his coddling parents who held him up as the “golden child” next to Phyllis, not even a boy, Marty was further sheltered by being Jewish. Such a myopic community as it is (especially in New York), Marty was perhaps bound to run into Ike eventually. But unlike Ike, Marty does not fall under the stereotype of being the money-grubbing, constantly haggling Yenta that Ike is. Not to mention an emotional Shylock, for he’s sure to collect on his interest of “helping” Marty despite being paid to do so. Marty instead embodies another Jewish stereotype: neurotic, guilt-ridden, prone to anxiety (therefore “stomach issues”), socially awkward and deemed by Dr. Ike to have some kind of Oedipus complex. Having caught Marty at a particularly vulnerable moment in his life—what with his parents just dying and his ex trying to shake him down for an all-expenses-paid trip to Mexico—Ike sees his “in” to latch on like a leech…permanently.

The only obstacle? Phyllis. As someone who now fulfills the “maternal” role entirely for Marty, she is not without her strong influence (though not for long on Ike’s watch). Especially since she also works at Associated Fabrics Corporation (the family business Marty inherited)—though it’s never quite clear what, exactly, her job title is. As for Marty, the newly-minted CEO, Ike insists he start acting the part by making some changes around AFC. This extends well beyond merely painting his office an obnoxious shade (to the tune of “Gloria”); it also means eventually hiring Ike as an “industrial psychologist” so he can imbue Marty’s team with as much confidence as he has within Marty. Or, more plainly, so he can find new ways to waste Marty’s money with his little “office improvements” that include a highly elaborate (and expensive) espresso machine.

Ike’s only real “counsel” for the team is that “there are no problems, only solutions.” It’s one of those annoying platitudes in the vein of “mind over matter.” Easy to say to someone until they’re, oh, laid up in the hospital. Like Marty ends up being in 2010 after being diagnosed with a hernia. In fact, it is in 2010 that the story commences (after a brief scene of Marty engaging in some beekeeping later on). That was the year Marty’s eyes were at least somewhat opened to the reality that Ike never gave an actual shit about him.

In this instant, the “hard to watch” quality of The Shrink Next Door intensifies as Marty comes to terms with what a fool he’s been all these decades. Something that many people have been forced to realize about themselves when a relationship at last comes to its overdue end. While the extent of what Ike manages to foist upon Marty is not common, per se, the difficulty in seeing it unfold—as well as the sympathy we feel toward Marty—is a direct result of our own unique memories of being bamboozled. Something we can’t help but blame ourselves for, our own stupidity, as it were (or, as Radiohead phrased it, “You do it to yourself, you do. And that’s what really hurts”). Because it is often very stupid to trust anyone with our emotions, so prone to backfiring as that is. In fact, Phyllis asks Marty not if he’s angry at Ike, but angry at himself. For allowing such a horrific fate to befall him at the hands of someone else. Someone he at least partially allowed to manipulate with such effective tenterhooks. Or puppet strings, if you prefer…since that is what the poster design for the podcast uses.

Anyone who has ever been fresh off the boat in Marty’s town of NY is likely to feel an especial pang while seeing the harrowing ordeal unfold. And it isn’t just because New York is filled with people trying to rip you off, financially or otherwise (and often won’t even bother with the pomp and circumstance of a “long game” emotional rape such as Ike’s), it’s that, in so many cities, where people are more prone to seeking some kind of genuine human connection, those very humans prove why being a shut-in remains more than a COVID-spurred lifestyle, but something that could literally save a person millions of dollars.

As for the psychology industry, The Shrink Next Door does little to shine a positive light on it, most notably when the last episode concludes with the caption, “Marty has never returned to therapy.” And why would he? Didn’t he funnel enough into it for more than several lifetimes? In this regard, the “unpleasant” subject matter of how much someone can truly “care” about another human being when they’re actually paid to do it (even though that doesn’t always ensure “caring”) comes into play. How much of it is ego-based versus “concern”-based? And this is why the show is likely the hardest of all for shrinks to endure themselves as they watch some form of their own latent God complex unfurl in the most id-like manner.