Despite the fact that, in the present, so much of one’s identity is wrapped up in the “profiles” of social media (a.k.a. the internet)–as though these genuinely say something about who you “are”–the mid-90s genesis of this pervasive, all-consuming black hole of an entity seemed already to foresee the insidious path it could (and would) take.

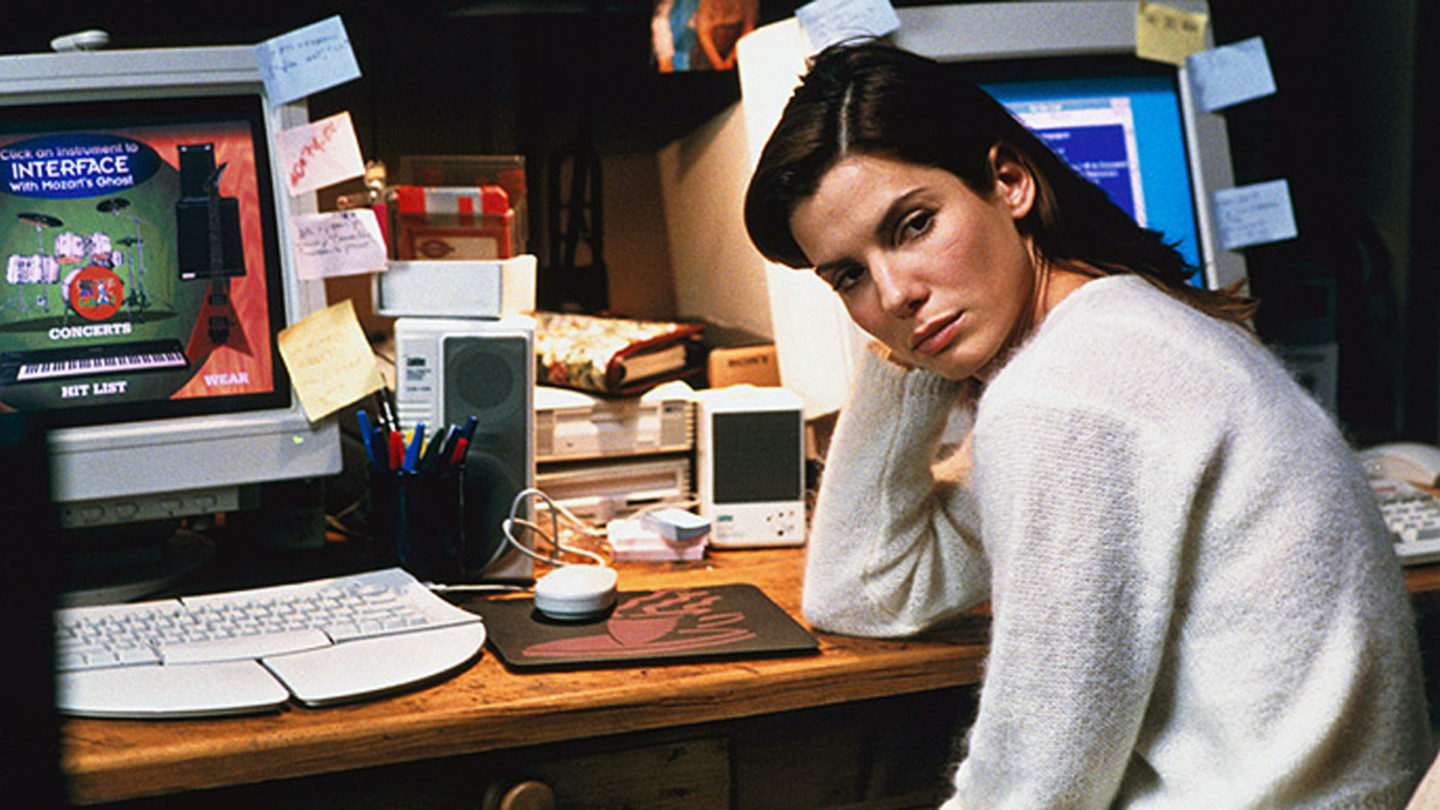

The Net‘s director, Irwin Winkler (more known for his producing skills before branching out more whole-heartedly into directing with late 90s/early 00s cheese such as At First Sight and Life As A House) might not have been as aware of this as the film’s co-writers, John Brancato and Michael Ferris, who deliver their manifesto on the perils of a society entirely reliant on computer-based systems and records through the pretty package of program analyst Angela Bennett (Sandra Bullock). Because, after all, by Hollywood standards, if a female character has to be a dweeb, she still has to be a fuckable dweeb if you quote unquote squint your eyes hard enough.

In point of fact, the character of Bennett is something of a beta test for what would be one of Bullock’s most memorable roles: Gracie Hart in Miss Congeniality. For, just as Hart, Bennett is antisocial, prefers ordering food in (Bennett’s preference being pizza.net–because we’re expected to believe someone with Bullock’s physique can eat like that, sit on her computer all day and still have a six-pack) and would rather hide behind the passion of her work than nurture any actual relationships–whether platonically or romantically. That she works from home and executes all of her interactions (few though they may be) virtually soon makes her a target of the very thing she loves the most: the internet. Or, more specifically, the hackers that have been monitoring her. Including her chatroom conversations with the likes of screen names/people in the ether called “CyberBob” and “Iceman,” telling them some of her most personal thoughts and life events. Including her upcoming vacation to Mexico. Because, perhaps sensing somewhere deep down that she ought to reconnect with nature, Bennett decides to embark upon a journey to Cozumel (because all L.A. dwellers have a soft spot for Mexico as a close enough but far enough vacation milieu).

Yet right before leaving she is contacted by a fellow employee at Cathedral named Dale (Ray McKinnon) who works at the San Francisco (forever hub of tech bullshit) headquarters. Presenting her with an intriguing bug on a webpage for a band called Mozart’s Ghost, Dale sends her a floppy disk via FedEx (yes, that might be one of the most 90s sentences ever uttered) so she can see what he’s talking about for herself. And see what he’s talking about she does, clicking on the ominous pi symbol “secretly” located at the lower righthand corner of the screen. Upon clicking on it, a glitchy government webpage demanding a password flickers angrily before her. Angela asks why he doesn’t just get rid of the glitch and move on, to which he replies he wants to meet with her in person to discuss the reason why. Assuring her he can chopper in from San Francisco in time for her to still make her flight, Dale’s navigation system is hacked so that he doesn’t notice until it’s too late that he’s about to crash into a tower.

“Oh well” Angela assumes when he doesn’t show up before it’s time for her to leave for the airport, where her flight just so happens to be delayed or hijacked (was that ever really a status in the 90s?) or cancelled thanks to a haywire glitch much like the one that has just caused a crash on Wall Street because of flickering and indecisive screen information. Angela doesn’t think much of it as she waits for a resolution, all while a lurking looming presence above watches her.

Once “safely” in Cozumel, Angela delivers on her cyberchat promise of it being “just me, a beach and a book.” This told to Iceman after his lament, “No one leaves the house anymore. No one has sex. The Net is ultimate condom.” Foreshadowing of what the twenty-first century would have in store for humanity indeed.

But, still back in the 90s, Angela can’t help but prove Iceman wrong in her attraction to fellow lone traveler Jack Devlin (Jeremy Northam) when he just so “happens” to order her favorite drink–a Gibson–while on the beach near her. It also helps his cause that he has a very snazzy laptop protruding from his bag to doubly encourage her falsely developing notion that he’s “just like” her. Once their conversation is struck and he proceeds to wax poetic about how pathetic they are for being on the most beautiful beach in the world yet still somehow only concerning themselves with “where can I hook up my modem?,” Angela is, in turn, hooked. As though the literal man of her cyberchat dreams has fallen directly into her lap.

Of course, it becomes steadfastly apparent that Jack, embodying the telltale 90s movie villain characteristics of both smoking and being British, is no good. Alas, like so many women long before the time of the internet’s nascence, Angela has to learn this the hard way after letting him inside of her. Escaping from him on a shoddy Nissan-motored (not the best product placement for the brand) dinghy, Angela crashes into some rocks and gets knocked out for three days (maybe never leaving the house was a better idea). This leaves Jack and his co-conspirators in cyberterrorism plenty of time to scrub her identity and present her with what sounds like an old lady communist one: Ruth Marx. For his added sick cyberterrorist pleasure, Jack slaps her with a rap sheet that includes prostitution and narcotics use, making her even more wary of bothering to convince the police of the plot against her. After all, why should they believe her when a computer never lies?

This eerie falsity as fact phenomenon hits Angela like a ton of virtual bricks when she winds up in prison, delivering the all too prescient monologue to her court-appointed lawyer that is as follows: “Just think about it. Our whole world is sitting right there on a computer, everything: your DMV records, your social security, your medical records. It’s all right there. Everyone is stored in there. It’s like this little electronic shadow on each and every one of us, just begging to be screwed with. They’ve done it to me and they’re gonna do it to you.” The “they” in question is helmed by a corporate technology titan by the name of Jeff Gregg (Gerald Berns), the sort of peak example of a rich person having enough time and privilege on his hands to create a problem that he can then supply (and profit from) the solution for: computer virus protection a.k.a. Gatekeeper. But with Angela wise to the fact that Gatekeeper’s antivirus software deliberately has a backdoor that can not only access people’s information, but also cause the virus that makes them think they need the software in the first place, she suddenly feels all icky about the internet.

To amplify the poeticness of her quickly realizing her human error in remaining so isolated by design for all these years, her own mother, the only person who would be able to identify her by sight apart from her former shrink and paramour, Alan (Dennis Miller), has Alzheimer’s. It’s pretty clear the symbolism here is that her mother’s mind has been wiped as effectively as the real Angela Bennett’s identity. And that if she had invested more time in other people with a better functioning hippocampus, she might have been spared all this drama. It puts everything into stark perspective for her as she gains an erstwhile lacking exaltation of the tangible. Reconciles that while interactions with humans can be both daunting and unsatisfying, it elicits more of a connection than a connected modem (again, 90s lingo).

To the plot point of the Praetorians hacking into both government and big business mainframes, The Net proved to be incredibly prophetic there as well–though it would turn out to be the 80s movie villain trope of the Russians tampering with U.S. political affairs instead of the latter’s own kind (because for Americans, tampering with their own kind remains a more tactile task in the form of guns). But regardless of what nationality cyberterrorists are, The Net makes it undeniably patent–well before anyone could know the full weight of the internet–that to surrender one’s psyche to the “world wide web” is a risk on par with how some cultures (particularly Native Americans) once thought that a click from a camera could steal their soul. With the internet, however, one click of a mouse can steal your identity. Whether literally or figuratively (with regard to that aforementioned trend of people as profiles trying so hard to curate something–not someone–likable). And if they don’t take your identity, they’ll simply chop up parts of it by mining your data in order to sell you back the things you gave to them for free simply by using a computer.

So all in all, those on “the inside” circa 1995 had to have known on some level that if a movie like The Net was made in the germinal phases of mass internet use, how could it possibly not get scarier as time wore on and the internet advanced (while its users have appeared to do the opposite)?