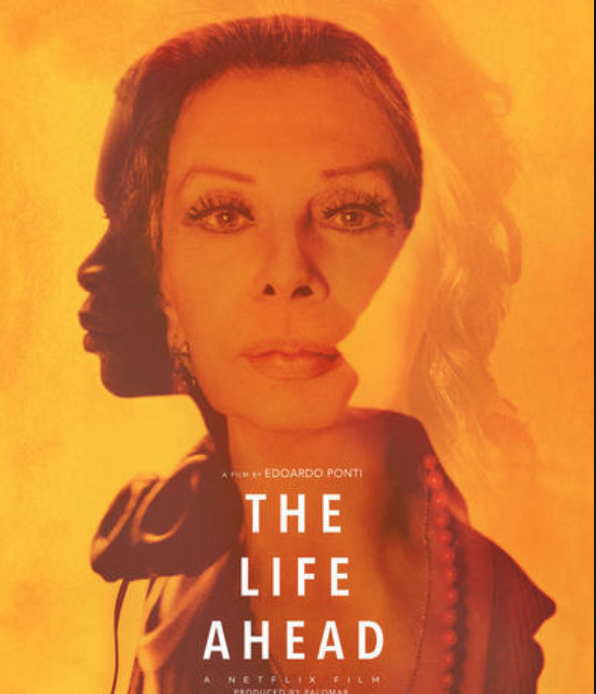

Perhaps for no one else would Sophia Loren come out of her unspoken retirement than her own son, Edoardo Ponti. Her youngest son, Ponti possesses that rare blend of having instinctual intuitiveness about filmmaking and the expensive education to fortify it. A product of USC film school, his best remembered movie is 2002’s Between Strangers, also starring La Loren (who would again appear in a short film of Ponti’s in 2014 called La Voce Umana). For what is the point of having an iconic Italian actress as your mother if you’re not going to use her talent to complement your own?

In The Life Ahead, however, it is more than just Loren’s acting prowess at play. Her young co-star, Ibrahima Gueye, who plays Momo (short for Mohamed), gives her plenty to play off of. And it starts the instant Momo homes in on his target, Madame Rosa (Loren), for her feebleness and vulnerability. She’s the perfect victim to steal from–which is exactly what Momo does as he rips her bag (filled with valuable candlesticks) off her shoulder and makes a run for it. Taking his bounty back to the house he lives in–a sort of unofficial orphanage run by Dr. Coen (Renato Carpentieri)–Momo tries to conceal it from his guardian. But it is not to be. What’s more, Dr. Coen has some other business to attend to after calling Momo out for the stolen merchandise, getting him to confess who it belongs to and then taking him to Madame Rosa with the additional purpose of asking if she’ll watch over him for several weeks, maybe months.

Her response is an adamant no, as only Loren, in all her Southern Italian gesticulating and staring daggers brilliance, can deliver. But Dr. Coen has ways of making her come around–namely, the offer of 750 euros a month for her trouble. She concedes, but that doesn’t mean she’s going to act as affectionately toward him as she does to the other kids under her roof, Babu and Iosef. Which is why she relegates Momo to the least “room-like” room, a small “shithole” with nothing more than a bed and a sink in it. What did he expect, she demands when he starts complaining. After all, he’s still the same “rotten to the core” child who stole from her.

As for Momo, who was initially averse to giving in to being put in Madame Rosa’s care, it is a local Pugliese drug dealer whose eye is caught by the boy’s drive and brazenness, that encourages him to choose her over Social Services. That way, he won’t be as intensely monitored. And indeed, it becomes quickly apparent that, despite her desire to be a strict taskmaster, Madame Rosa is succumbing to the frailties of old age, most noticeably some form of dementia that has her occasionally spacing out into a deep trance (which will devolve into more sinister forms of remembrance of things past as the movie progresses). As for Momo, he uses her laissez-faire tendencies to his drug dealing advantage. “I’m young and I’ve got my whole life ahead of me,” Momo narrates halfway through the movie, adding, “I’m not going to lick happiness’ ass. If it shows up, great. If not, who gives a shit? Me and happiness aren’t from the same race” (an easily interpretable reference to it belonging to the race of white folk instead).

This doesn’t mean Madame Rosa won’t find him some more legitimate work in the store of a local shop owner as well (for she’s unaware of the occupation he already has). Momo is expectedly unenthusiastic but goes along with it, by now used to being pimped out in some way by adults. Fittingly, Madame Rosa is an ex-prostitute who decided to retire at one point and instead collect cash from working whores by watching over their children. After all, not everyone is a believer that taking care of kids is “a gift.” One of the children, Babu, belongs to a trans prostitute named Lola (Abril Zamora). At certain moments, perhaps because of this trans character (who is, in fact, Spanish), The Life Ahead takes on the tint of an Almodóvar movie. But it promptly returns to the core of what Southern Italianness embodies: the tragicomic irony of existence. Finding beauty in the most squalid of circumstances. And in the most unlikely of people.

Of course, many Italians have yet to take on the “openness” of mind Madame Rosa does with regard to her attitude about migrants. And certainly, many Southern Italians would not be entusiasta about caring for the child of a Senegalese migrant–so maybe this film should be required viewing if not for the nation, then at least for Matteo Salvini.

A scene in which Madame Rosa emerges from Dr. Coen’s office with Momo in tow finds them encountering the police rounding up a crowd of undocumented migrants–complete with a harrowing moment when we see a child being literally ripped from her mother’s grasp. Madame Rosa pulls Momo away abruptly from the unpleasant view, as though to indicate that will not be his fate while he’s with her. Alas, time is merciless and spares not even the strongest of wills (except for that ghost in The Haunting of Bly Manor).

To that end, in Italian, the book by Romain Gary is pointedly called La vita davanti a sé (also the title of the film), meaning The Life Ahead of Us. In its English translation, dropping the “of us” seems to connote the inevitable outcome of the story, with Momo being the one who will soldier on without Madame Rosa in his life. In this sense, while Loren is from an age in which Italy “belonged” to Italians, both she and Ponti (through the mouthpiece of Gary’s work) are seeming to gently explain (in their own thinly veiled manner) to the country that the future of the boot is destined to both look more like and be politically influenced by the migrant demographic.

Hence, the wielding of Madame Rosa’s past. The fact that she is still very much haunted by the PTSD (to use understatement) of her time spent in a concentration camp when she was just a little girl is a deliberately pointed aspect of the tale. And it is her background as a Holocaust survivor with which we’re posed the question: how can anyone who endured such unspeakable cruelty–or even anyone aware of that part of history–ever act or wish such treatment on another human being just because they’re not “the same”? Not part of some, for all intents and purposes, “Aryan” race of “pure” Italians.