The slow burn of Relic is almost as slow-burning as time itself, until, all at once, the escalation becomes unstoppable, working at a breakneck pace until it’s too late to realize what’s happened. This, too, is like time itself, particularly when it comes to age creeping up on you with as much of an element of surprise as bankruptcy. As the directorial and screenwriting debut of Natalie Erika James (who co-wrote with Christian White), a producer credit from Jake Gyllenhaal automatically gives the film an added seal of approval for a first-timer, and it doesn’t take long to see why.

After the disappearance of the elderly Edna (Robyn Nevin), prone to bouts of dementia, her daughter, Kay (Emily Mortimer), and granddaughter, Sam (Bella Heathcote), show up to her remote house to investigate. Kay, who admits she’s not sure what she’s supposed to be doing and that she’s glad Sam is there, has an ostensibly strained relationship with her own mother. One that led her to go many weeks without talking to her and to ignore her pleas when she last called, describing an intruder in the house. For Kay, it has so long been easy to write off what she’s said as delusion that she can’t even fathom something bad actually happening. When it does, of course, she can’t help but feel more than a tinge of guilt.

In the meantime, she finds herself berating Sam for her own life choices, asking her if she plans to work in a bar the rest of her life rather than going back to school and completing her college education. Sam shrugs and says maybe that is what she plans to do, simply work in a bar. And in this moment we can see the familial pattern of wanting to push one’s own fate and agenda onto the offspring that might be allowed to start anew, try something different. Yet the prior generation’s expectations and constantly palpable disappointment if you don’t adhere to their own previously well-trodden path seem always to get inside one’s head. Like a rot that just won’t be flushed out. The film’s summary itself highlights the fact that Edna and her progeny are “haunted by a manifestation of dementia that consumes their family’s home.”

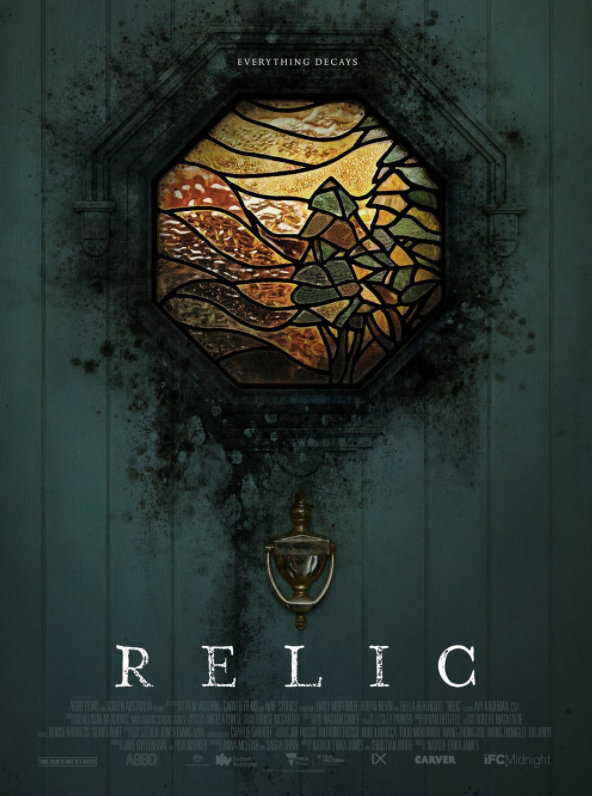

It is a manifestation that Kay keeps having nightmares about while staying in the house, seeing the rotting corpse of her great grandfather, who himself was known to have gone crazy from the dementia he had. At the time of his death, there was still a shack-like edifice in the woods just beyond the main house. This was where her great grandfather lived as he descended into madness. The same window from that structure (after it was demolished) was used in the new house as an homage to “posterity,” one supposes. But it is also the source of the fast-spreading mold throughout the space. With the tagline, “Everything decays,” we know James isn’t referring only to the inanimate. But to the body itself as it grows old, ages into a state of decrepitude that few things except money or being Italian can prevent. When humans reach this state, it no longer matters that they have loved ones–the burden of their existence becomes too great, as we’ve been shown time and time again in the treatment of the elderly.

The most glaring example of late has been the outbreaks of coronavirus in nursing homes, particularly in North America. The maltreatment and level of neglect that led to these facilities bearing the brunt of Covid statistics speak volumes about how we see the aged: as being valueless. As the Director-General of WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has noted of the chilling callousness with which the virus has been viewed in terms of the “Oh whatever, it’s only killing off old people” philosophy it has been met with: “Every individual life matters. If we don’t care about one individual, whether old or young, then we’re not serious. And that’s why we are saying this is a moral decay, a moral decay of the society.” Telling, then, that Relic is all about decay both literally and figuratively. And indeed, society has no interest in sustaining the lives of those who cannot work, continue to be part of the suffering and misery that will generate revenue for a well-oiled economy.

It’s almost an affront to people that the old should enjoy so much free time after decades of toil. To this end, it must be posited that the contempt and lack of patience or respect for the elderly comes, in some sense, from a place of jealousy on the part of those still damned to years of working, and also knowing that, the more time passes, the less there will be in the collective pot called social security. Not only that, but there is a jealousy over the general “cushness” of the elderly lifestyle. For those such as Edna living in a posh house the likes of which many millennials can only dream of is a symbol of the excess and selfishness of previous generations that have manifested more globally in the fallout of climate change. The thoughtless pillaging of the environment by rabidly capitalist boomers mucking about in fossil fuels as though it were La Mer.

So yes, in this sense, there is an increased underlying resentment between the au courant generation of youth and those “olds” that came before them. Its own form of rot seeping into the dynamic of how the elderly are treated and regarded (case in point, the taunting and patently ageist, “OK Boomer”). As for the literal rot that has seeped into Edna (demonstrated by the “bruise”-like blackness at the center of her chest), it possesses her to say and do mean-spirited things. For instance, as Sam walks in on her talking to herself (but really to the spectral black figure that occasionally crops up throughout the film), she hears her railing, “They’re pretending. You know what I think? I think they’re just waiting. They’re just waiting for the day. I think they’re hoping I’ll go to sleep and I’ll never wake up. Then they’ll dump me in the ground to rot.”

Possessed by the black mold “manifestation of dementia” or not, Edna isn’t wrong to feel this sense of paranoia about being both unwanted and used for what she can give as an inheritance once she’s dead. She’s only going by what centuries of watching how the youth treat their elders have taught her, resulting in this venomous reaction filled with suspicion.

The fact that those who dare to age are, indeed, tacitly classified as relics (meaning “an object surviving from an earlier time,” with synonyms including “antiquity,” “fossil,” “corpse,” “remains” and “cadaver”) speaks to the way in which society is responsible for relegating (relic-gating, rather) them so far to the fringe that they have their own holding facilities to go to until they “finally” die. Extinguished either by the physical side effects of their age or the loneliness that comes with being in such a situation.

As the stunning conclusion to Relic occurs, in the literal sense, James is saying, yeah, Alzheimer’s (and most other forms of mental and physical deterioration) is inherited. But at the deeper level, it is a comment on how we are all doomed to absorb the emotional baggage and trauma of the family members that came before us. This, in part, is why we can’t help but eye-rollingly treat the old with something very akin to malice. Until, that is, we perhaps make peace with the empathetic idea that we’re all damned to end up in the same position–six feet under. Except, soon enough, we’ll even have as a reason to resent previous generations the fact that they were able to secure a grave plot via the formerly accepted phenomenon of body disposal that was an overtly egregious waste of space.