For those who applaud it, any contempt expressed for the latest iteration of Mean Girls is likely to be met with the ageist rebuke of how it’s probably because you’re a millennial (granted, some millennials might be enough of a traitor to their own birth cohort to lap up this schlock). As in: “Sorry you don’t like it, bitch, but it’s Gen Z’s turn now. You’re just jealous.” The thing is, there’s not anything to be jealous of here, for nothing about this film does much to truly challenge or reinvent the status quo of the original. Which, theoretically, should be the entire point of redoing a film. Especially a film that has been so significant to pop culture. And not just millennial pop culture, but pop culture as a whole. Mean Girls, indeed, has contributed an entire vocabulary and manner of speaking to the collective lexicon. Of course, reinventing the wheel might be the expectation if this was a truly new version. Instead, it is merely a translation of the Broadway musical that kicked off in the fall of 2017, right as another cultural phenomenon was taking shape: the #MeToo movement.

This alignment with the repackaging of Mean Girls as something that a new generation could latch onto and relate with seemed timely for the heralding of a new era that not only abhorred flagrant sexual abuse against women, but also anything unpleasant whatsoever. It quickly became clear that a lot of things could be branded as “unpleasant.” Even some of the most formerly minute “linguistic nuances.” This would soon end up extending to any form of “slut-shaming” or “body-shaming.” Granted, Fey was already onto slut-shaming being “over” when she tells the junior class in the original movie, “You all have got to stop calling each other sluts and whores. It just makes it okay for guys to call you sluts and whores.” (They still seem to think it’s okay, by the way.)

Having had such “foresight,” Fey was also game to update and tweak a lot of other “problematic” things. From something as innocuous as having Karen say that Gretchen gets diarrhea on a Ferris wheel instead of at a Barnes & Noble (clearly, not relevant enough anymore to a generation that gets any reading advice from “BookTok”) to removing dialogue like, “I don’t hate you because you’re fat. You’re fat because I hate you” to doing away entirely with that plotline about Coach Carr (now played by Jon “Don Draper” Hamm) having sexual relationships with underage girls.

What Fey has always been super comfortable with (as most people have been), however, is ageist humor (she has plenty of anti-Madonna lines to that effect throughout 30 Rock). For example, rather than Gretchen (Bebe Wood) telling her friends that “fetch” is British slang like she does in 2004, she muses that she thinks she saw it in an “old movie,” “maybe Juno.” Because yes, everything and everyone is currently “old” in Gen Z land, though 2007 (the year of Juno’s release) was seventeen years ago, not seventy. This little dig at “old movies” is tantamount to that moment in 2005’s Monster-in-Law when Viola Fields (Jane Fonda) has to interview a pop star (very clearly modeled after Britney Spears) named Tanya Murphy (Stephanie Turner) for her talk show, Public Intimacy. Finding it difficult to relate to Tanya, Viola briefly brightens when the Britney clone says, “I love watching really old movies. They’re my favorite.” Viola nudges, “Really? Which ones?” Tanya then pulls a “Mean Girls 2024 Gretchen” by replying, “Well, um, Grease and Grease II. Um, Benji, I love Benji. Free Willy, um, Legally Blonde…uh The Little Mermaid.” By the time Tanya says Legally Blonde (four years “old” at the time of Monster-in-Law’s release), that’s about as much as Viola can take before she’s set off (though Tanya blatantly showcasing her lack of knowledge about Roe v. Wade is what, at last, prompts Viola’s physical violence). Angourie Rice, who plays a millennial in Senior Year, ought to have said something in defense of Juno, but here she’s playing the inherently ageist Gen Zer she is. Albeit a “geriatric” one who isn’t quite passing for high school student age. Not the way Rachel McAdams did at twenty-five while filming Mean Girls.

To that point, Lindsay Lohan was seventeen years old during the production and theater release of Mean Girls, while Angourie Rice was twenty-two (now twenty-three upon the movie’s theater release). Those five years make all the difference in lending a bit more, shall we say, authenticity to being a teenager. Mainly because, duh, Lohan was an actual teenager. And yes, 2004 was inarguably the height of her career success. Which is why she clings on to Mean Girls at every opportunity (complete with the Mean Girls x Wal-Mart commercial). Thus, it was no surprise to see her “cameo” by the end of the film, where she takes on the oh so significant role of Mathlete State Championship moderator, given a few notable lines (e.g., “Honey, I don’t know your life”—something that would have landed better coming from Samantha Jones) but largely serving as a reminder of how much better the original Mean Girls was and that the viewer is currently watching a dual-layered helping of, “Oh how the mighty have fallen.”

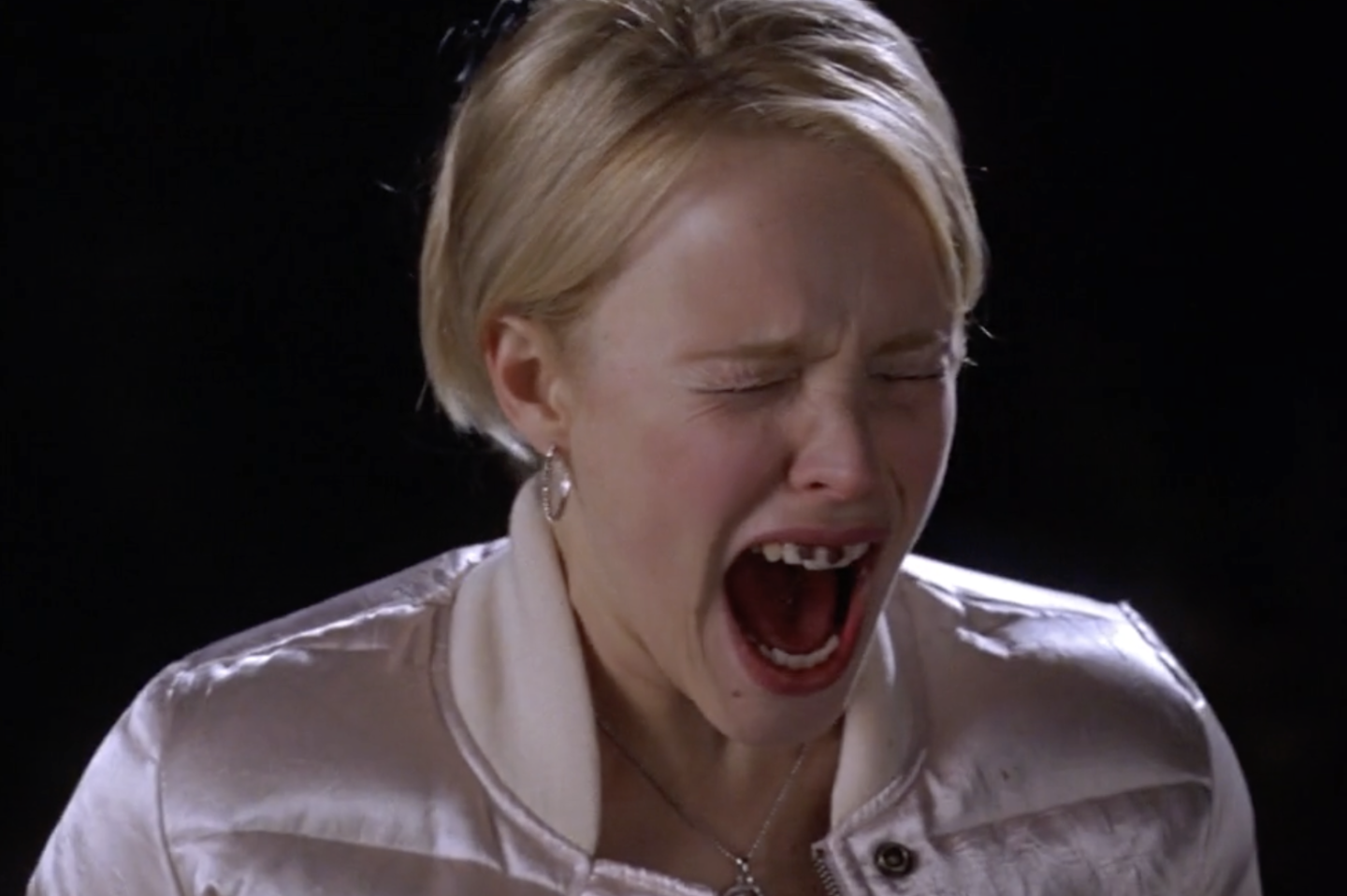

While the musical angle is meant to at least faintly set the 2024 film edition apart from the original, it’s clear that Tina Fey, from her schizophrenic viewpoint as a Gen Xer, has trouble toeing the line between post-2017 “sensitivity” and maintaining the stinging tone of what was allowed by 2004 standards. Although Gen Z is known for being “bitchy” and speaking in a manner that echoes the internet-speak amalgam of gay men meets AAVE, any attempt at “biting cuntery” is in no way present at the same level it was in 2004’s Mean Girls. And a large part of that isn’t just because “you can’t say shit anymore,” but also because the meanness of the original Regina George is completely washed out and muted. This compounded by the fact that Reneé Rapp is emblematic of a more “body positive” Regina. In other words, she’s more zaftig than the expected Barbie shape of millennial Regina. Perhaps this is why any acerbic comments on Regina’s part about other people’s looks are noticeably lacking. For example, in the original, Regina tells Cady over the phone, in reference to Gretchen (Lacey Chabert), “Cady, she’s not pretty. I mean, that sounds bad, but whatever.” Regina might say the same of the downgraded looks of the Mean Girls cast as a whole… Let’s just say, gone are the days of the polish and glamor once present in teen movies. And yet, there is still nothing “real” about what’s presented here in Mean Girls 2024. Because, again, it struggles too much with the balancing act of trying to be au courant with the fact that it was created during a time when people (read: millennials) could withstand such patent “meanness.”

In the climate of now, where bullying is all but a criminal offense resulting in severe punishment, Mean Girls no longer fits in the high school narrative of the present. This is something that the aforementioned Senior Year gets right when Stephanie (Rebel Wilson) returns to high school as thirty-seven-year-old and finds that Gen Z seems to care little about the rules of social hierarchy she knew so well as a teenage millennial. And the rules Regina George’s mom likely knew as well. Alas, Mrs. George becomes a pale imitation of Amy Poehler’s rendering, with Busy Philipps trying her best to make the role “frothy,” even when she warns Regina and co. to enjoy their youth because it will never get any better than it is right now for them (something Gen Z clearly believes based on an obsession with people being “old” that has never been seen to this extent before). The absence of her formerly blatant boob job also seems to be an arbitrary “fix” to the previous standards of beauty that were applauded and upheld in the Mean Girls of 2004 (hell, even the “fat girl” who sees Regina has gained some extra padding on her backside is the first to mock her by shouting in front of everyone, “Watch where you’re going, fat ass!”).

To boot, the curse of having to “update” things automatically entails the presence of previously unavailable technology. This, of course, takes away from the bombastic effect of Regina scattering photocopies of the Burn Book pages throughout the entire school, instead placing the book in the entry hallway to be “discovered.” And yes, the fact that the Gen Z Plastics would be using a tactile object such as this is given a one-line explanation by Regina when she asks if they made the book during the week their phones were taken away. Again proving how this “translation” doesn’t hold the same weight (no fat-shaming pun intended) or impact as before.

More vexingly still, without the indelible voiceovers from Cady, the movie becomes a hollow shell of itself, and not just because it’s now a musical lacking the punch of, at the very least, some particularly memorable lyrics (and no, “Not My Fault” playing in the credits isn’t much of a prime example of that either). And so, those who remember the gold standard of the original movie will have to settle for conjuring up the voiceovers themselves while watching (e.g., “I know it may look like I’d become a bitch, but that was only because I was acting like a bitch” and “I could hear people getting bored with me. But I couldn’t stop. It just kept coming up like word vomit”). But perhaps Fey felt that the “storytelling device” of Janis ʻImi’ike (Auliʻi Cravalho)—formerly Janis Ian—and Damian Hubbard (Jaquel Spivey)—formerly just Damian—telling it through what is presumed to be a TikTok video (this, like Senior Year, mirroring a trope established by Easy A) would be enough to both “modernize” the movie (along with Cady being raised by a single mom instead of two married parents) and compensate for its current lack of signature voiceovers.

Some might point out that there’s simply no room for voiceovers in a musical without making the whole thing too clunky. Which brings one to the question of why a musical version instead of a more legitimate reboot had to be made. Well, obviously, the answer is: money. Knowing that the same financial success of the musical would be secured by an effortless transition to film. One that ageistly promises in the trailer: “Not your mother’s Mean Girls.” Apart from the fact that it doesn’t deliver at all on any form of “raunch” that might be entailed by that tagline, as Zing Tsjeng of The Guardian pointed out, “Your mother’s? Tina Fey’s teen comedy was released nineteen years ago. Unless my mother was a child bride, I’m not sure the marketing department thought this one through.”

But of course they did. And what they thought was, “Let’s throw millennials under the bus like Regina and focus our money-making endeavors on a fresher audience.” That fresh audience being totally unschooled in the ways in which Mean Girls is a product of its time. And so, is it really supposed to be “woke” to change the indelible “fugly slut” line to “fugly cow”? As though fat-shaming is more acceptable than slut-shaming (which also occurs when Karen [Avantika] is derided by both Regina and Gretchen for having sex with eleven different “partners”—the implication perhaps being that maybe some of them weren’t boys). And obviously, Regina saying, “I know what homeschool is, I’m not retarded” had to go. The phrase “social suicide” is also apparently out (even though Olivia Rodrigo is happy to reference it in “diary of a homeschooled girl”). In general, all “strong” language has been eradicated. Something that becomes particularly notable in the “standoff” scene between Janis and Cady after the former catches her having a party despite saying she would be out of town. In this manifestation of the fight, gone are the harshly-delivered lines, “You’re a mean girl, Cady. You’re a bitch!”

Despite its thud-landing delivery, the messaging of Mean Girls remains the same. Or, to quote the original Cady (evidently an honorary Gen Zer with this zen anti-bullying stance), “Making fun of Caroline Krafft wouldn’t stop her from beating me in this contest. Calling somebody else fat won’t make you any skinnier, calling someone stupid doesn’t make you any smarter. And ruining Regina George’s life definitely didn’t make me any happier. All you can do in life is try to solve the problem in front of you.” Alas, Fey doesn’t solve the problem of bridging millennial pop culture into what little there is of Gen Z’s. At the end of Mean Girls 2024, the gist of Cady’s third-act message becomes (as said by Janis): “Even if you don’t like someone, chances are they still want to just coexist. So get off their dick.”

The thing is, Mean Girls 2024 can’t coexist (at least not on the same level) with Mean Girls. It’s almost like Cady Heron trying to be the new Regina George. That is to say, it just doesn’t work, and ends up backfiring spectacularly (though not from a financial standpoint, which is all that ultimately matters to most). Unfortunately, when Cady tells Damian at the end of 2004’s Mean Girls, “Hey, check it out. Junior Plastics” and then gives the voiceover, “And if any freshmen tried to disturb that peace…well, let’s just say we knew how to take care of it [cue the fantasy of the school bus running them over],” she added, “Just kidding.” And she was. Otherwise the so-called junior Plastics of Mean Girls 2024 wouldn’t be here, disturbing the millennial peace.

[…] was also after the news that she had been cast as Glinda in the film version of Wicked (because turning musicals based on movies into musical movies is all the rage now). A project that also consumed her enough for her to announce that she would not release new music […]

[…] sing “ballad of a home schooled girl” (a timely choice considering the then upcoming release of Mean Girls 2024). Although not exactly outfitted in “Courtney Love circa 1994” attire during this instance, the […]

[…] sing “ballad of a home schooled girl” (a timely choice considering the then upcoming release of Mean Girls 2024). Although not exactly outfitted in “Courtney Love circa 1994” attire during this instance, the […]

[…] a “Rodrigo trend” in trailers if also having “get him back!” played during the Mean Girls 2024 trailer is an indication…but hey, Wolpert did previously work on High School Musical: The […]

[…] a “Rodrigo trend” in trailers if also having “get him back!” played during the Mean Girls 2024 trailer is an indication…but hey, Wolpert did previously work on High School Musical: The […]

[…] for whatever reason, among the Gen Z crowd trying to lay claim to her the way they have with Mean Girls) has entirely superseded her brief bout with “cancellation” in 2020, after posting her infamous […]

[…] for whatever reason, among the Gen Z crowd trying to lay claim to her the way they have with Mean Girls) has entirely superseded her brief bout with “cancellation” in 2020, after posting her infamous […]