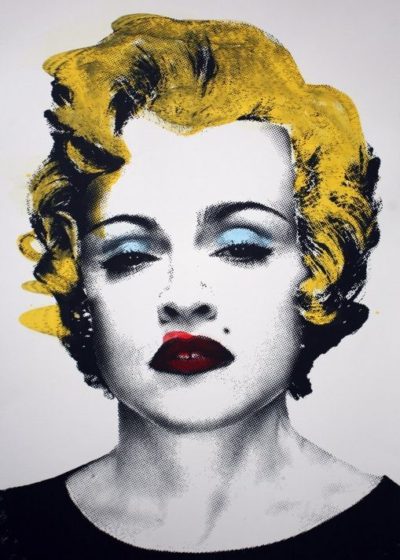

Andy Warhol, of course, had many philosophies. On fame, love, work, time. A large bulk of them being placed in 1975’s The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again). A “treatise,” of sorts, that even offered an entire chapter called “Beauty,” wherein Andy provided such pearls as, “I usually accept people on the basis of their self-images, because their self-images have more to do with the way they think than their objective-images do.” Of late, if anyone embodies that strong belief in self-image, it’s Madonna. At the same time, she has always projected her self-image onto the world (via that infamous confidence and bravado) to mirror back to her what she sees… even if admitting to not being a “conventional beauty.” But that never mattered because she was more “interested in being provocative and pushing people’s buttons.” Something she’s now doing by believing in her self-perception so much that she has decided to take control of her “airbrushing” (better known in Instagram-era parlance as “filters”).

With social media being the ultimate tool for celebrities to control their own narrative (in a way that Britney Spears never could in the 00s), part of that control most certainly also extends to image. And Warhol was the modern blueprint provider for what that would and could mean. He, of all people, understood where Madonna is currently coming from as she seeks to erase the imperfections because she can. Because she wants to still measure up to the photographs of the past—for, like Andy said, “The best thing about a picture is that it never changes, even when the people in it do.” Madonna has made it her mission to be one of those rare people who doesn’t change from the photos of yore… even if we can all notice the “slight alterations” she’s made to her exterior to achieve that effect.

Plus, one must not forget that “being attractive” is a primary aspect of the job description that comes with being famous. The fear of “losing beauty” is something even the most presently “nubile” of pop stars—from Billie Eilish to Olivia Rodrigo—will have to face eventually. The erstwhile Lolita of the late 90s and early 00s, Britney, has also shown how much that kind of pressure and scrutiny can weigh on a girl, overtly fixated on how she’s portrayed physically in paparazzi photos and recently getting candid about her Botox forays and how she was afraid her eyebrow was going to get stuck in place. But even before Brit, Warhol wanted to normalize plastic surgery, declaring, “Even beauties can be unattractive. If you catch a beauty in the wrong light at the right time, forget it. I believe in low lights and trick mirrors. I believe in plastic surgery.”

Madonna, who set the stage for a certain kind of lifelong vanity by modeling in her early days, certainly adheres to that need to constantly match her actual image to the one seen in photos. Something that also caused Marilyn Monroe to take her sweet time when it came to getting ready. After all, it’s as Warhol posited: “Beauties in photographs are different from beauties in person. It must be hard to be a model, because you’d want to be like the photograph of you, and you can’t ever look that way. And so you start to copy the photograph.” Obsessively.

Another aspect of Warhol’s philosophy on beauty that is only cursorily broached pertains to the undeniable tie between wealth and beauty. How being able to afford the products and the various accoutrements of the cosmetics industry are part of what makes a person appear that way, ergo another more recent platitude birthed into the internet ether: “you’re not ugly, just poor.” Warhol said it a bit less crassly back in the day with, “Being clean is so important. Well-groomed people are the real beauties. It doesn’t matter what they’re wearing or who they’re with or how much their jewelry costs or how much their clothes cost or how perfect their makeup is: if they’re not clean, they’re not beautiful. The most plain or unfashionable person in the world can still be beautiful if they’re very well-groomed.” And that Madonna is, exuding a bright, glowing whiteness (apart from just the one on her pale skin) that comes from taking regular rose petal-filled baths. So clearly, Warhol didn’t find much attractiveness in the homeless man on the street (rough trade potential or not).

But the part of Warhol’s philosophy that most clearly speaks to Madonna’s own when it comes to omission of flaws is when he recalls, “When I did my self-portrait, I left all the pimples out because you always should. Pimples are a temporary condition and they don’t have anything to do with what you really look like. Always omit the blemishes—they’re not part of the good picture you want.” And many would agree with him. Why include the flaws when a picture is supposed to depict the best possible version of yourself? Madonna has transferred this philosophy to any visible imperfections whatsoever on her face, transitory or not. Incidentally, she did used to have a pretty bad case of adult acne that flared up enough during the “Secret” video to warrant being filmed in black and white. However, this current predilection for “omission” goes far beyond acne. And yet, why should M be judged for projecting Andy Warhol’s philosophy in the twenty-first century? So long as she’s okay with occasionally being caught not looking quite like the self we see on social media.