Something happened long ago when celebrities were finally allowed the same democratizing outlet as every other plebe: “the tool” of social media. It “empowered” them in new and unprecedented ways that rendered tabloids and Perez Hilton-like blogs irrelevant. Because now it was possible to hear the truth from the horse’s mouth. Then again, the truth remains subjective most of the time regardless. For celebrities aren’t always the most adept at seeing things objectively, what with the ability they have to build a fortress around themselves from the outside world (and who wouldn’t? The masses are fucking brain-dead, often making equally as stupid people their gods). Despite the nullification of tabloid fodder, it hasn’t been until recently that the critic has been called into question by the culture that worships its celebrities. A culture that seems to be asking: what is the point of a critic if they don’t tout a famous person’s greatness? That critics in general are often written off as those who couldn’t succeed at doing something artistically bankable in their own life (playing into that whole “those can’t do, teach” adage) further adds to their general malignment by the public–both the fans and the famous.

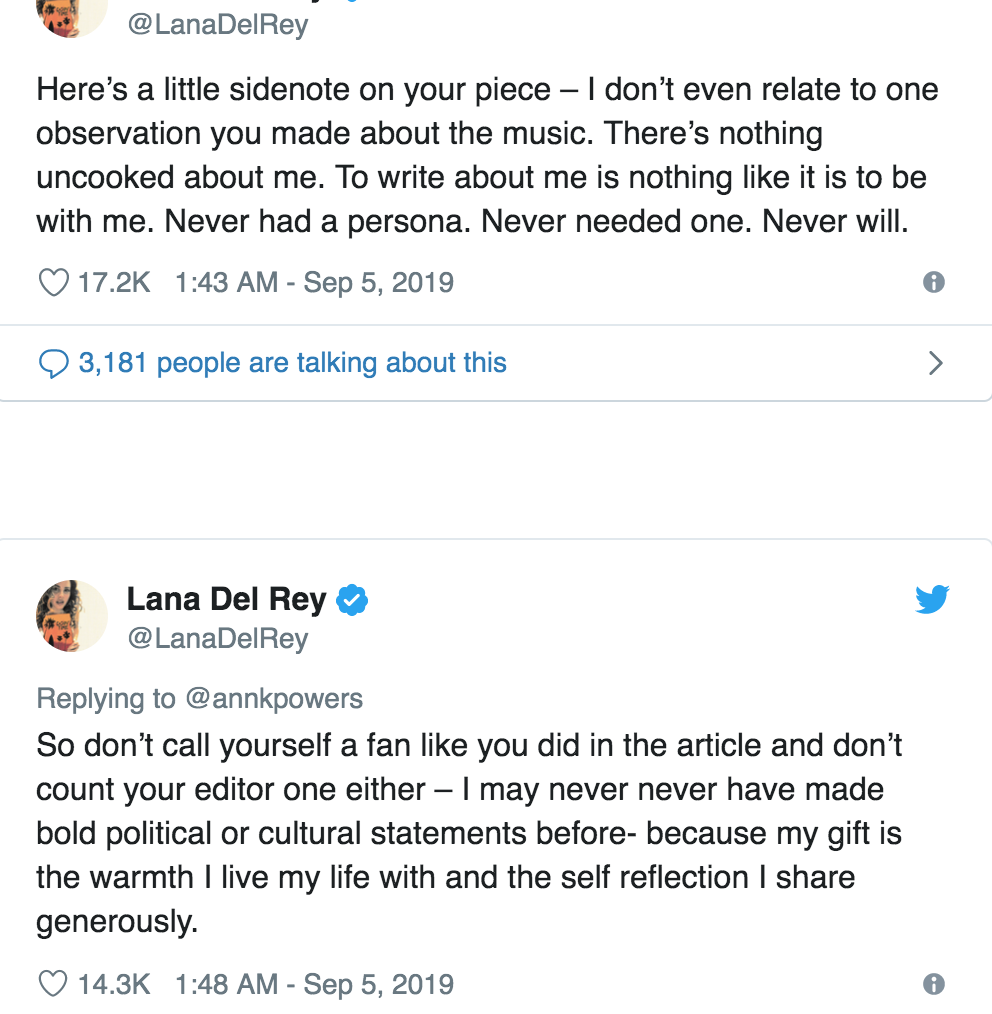

Ann Powers had the displeasure of being reminded of this on September 4th (Beyoncé’s birthday, of all days) when Lana Del Rey herself responded to her review of Norman Fucking Rockwell soon after it went live with the assessment: “Here’s a little sidenote on your piece–I don’t even relate to one observation you made about the music. There’s nothing uncooked about me. To write about me is nothing like it is to be with me. Never had a persona. Never needed one. Never will. So don’t call yourself a fan like you did in the article and don’t count your editor one either–I may never have made bold political or cultural statements before–because my gift is the warmth I live my life with and the self-reflection I share generously.” Barring the fact that Del Rey comes off as more of a pompous twat than Ann Powers in her review (gee Lana, thanks for so “generously” profiting from your “self-reflection” by selling it in the form of records), the obvious nerve it struck with her speaks to 1) how much she cares about NPR’s opinion and the one it disseminates to its listeners and readers and 2) how much the truth can hurt when it comes to calling her out for being essentially derivative with the luck of cinematic productions to render her lyrics perhaps more grandiose than they really are (e.g. “don’t make me sad, don’t make me cry”). Considering that this type of criticism hasn’t been leveled at her since the outset of her career, maybe it’s also giving her a touch of PTSD (as all things harkening back to a New York era do). What’s more, she’s gotten too comfortable with unanimous praise and pandering, the constant deification her fans imbue her with probably not helping on that front.

One thing Del Rey is accurate on with her snarky comment is that Powers really oughtn’t bother calling herself a fan. At least not with regard to the present definition of what a fan is: someone who will not question any of the “god’s” work that they’re worshipping. Will not bother with poking any holes in it because that would mean questioning scripture altogether, ergo the entire meaning of life. In a separate instance of a pop singer (because, yes, Del Rey is, even if she dabbles in other genres) lashing out directly at a critic this year was Madonna. She, too, took offense to an article in The New York Times Magazine called “Madonna At Sixty” written by Vanessa Grigoriadis–known far more for being an unbridled cunt than a writer of thoughtful pop criticism as Ann Powers is. Grigoriadis also talks a fair game in the article about being a fan of Madonna, in equally as backhanded ways, including, “Not everyone loved her later phases, like her 2012 hard dance album MDNA, probably best experienced at a foam party on Ibiza, but as a middle-aged mother who liked shaking off the week in the club from time to time, I remained by her side.” Jesus, what a passive aggressive bitch. It’s easy to take these comments as the artist herself would, for one doesn’t need to have an MFA in Literature to interpret tone.

This is precisely why the best thing for a critic to do in the climate of now is not bother with trying to insist that they’re a fan, but instead simply review the work without apology (which is what claiming to be a fan is in this context–“I’m a fan, but…”). Yet part of the reason why they seem to feel inclined to insert this caveat into their criticism is a direct result of the fear of what inevitably happens anyway: contempt for the review followed by a massive backlash as orchestrated by the celebrity herself, knowing full well that an army of minions are at their side to draw blood whenever they ask. That is the power of semi-direct communication with fans, who see this advanced twenty-first century connection to the one they worship as even more reason to believe.

Powers’ brand of criticism is increasingly from a bygone era, one that actually attempts to frame what seems to naysayers to be nothing more than another cycle of frivolous pop fare within the lens of the past. How we got here and why we’re listening to this now, why it comes across as so resonant to so many listeners. Had Powers stuck with this specific track as opposed to peppering in Grigoriadis-league comments, she might have eked by. Or if she had just been unbridled instead of passive aggressive, with grammatical errors to boot (this is when one is like, “Really? Clearly no one is reading this drivel at all past a certain point, not even the people who get paid to edit). As was the case with her critique of “Cinnamon Girl”: “The song feels more like you’re in a story, in someone’s head at a particularly unsure moment. A great songwriter, as we tend to understand that role, would offer a more coherent view. But for Del Rey, the mash-up of affects and references is the point. It is emotion’s actuality.” First of all, it’s effects. Secondly, say it loud and proud without dancing around the issue that Del Rey’s songwriting is, at its core, a pastiche-laden hot mess that gets recycled to the point of oblivion in her work (how many times can she repeat the same amalgam of colors, talk about red dresses or wax on about the fucking summer?). That’s arguably the most vexing aspect of Powers’ review: her reluctance to be unabashed in essentially telling Del Rey, “Bitch you ain’t Joni Mitchell.” For it was one sentence about being “uncooked” in particular that Del Rey refers to in her reply to Powers that cuts to the heart of what the critic is really saying: “There’s some moaning about how no one has ‘held me without hurting me,’ and half-formed thoughts about words she cannot speak. Compare this vague non-story to four lines randomly pulled from Mitchell’s 1972 song about her then-lover James Taylor’s heroin habit, ‘Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire,’ written when she was five years younger than Del Rey is now: Concrete concentration camp / Bashing in veins for peace / Cold blue steel and sweet fire / Fall into Lady Release. Mitchell’s lyric reads as poetic and incisive. Next to it, Del Rey’s feels uncooked. Musically, ‘Cold Blue Steel’ also strikes the listener as much more sophisticated, with its subtle arrangement and a melody that sinuously moves from folk to jazz.”

Yet she then seems to waver, holding back with her underlying worry about how Del Rey and her audience might react (which they did anyway) with the tacked on consolation, “Yet let Del Rey’s song sink in, and it offers its own revelations — sensual and emotional, like Mitchell’s, but less clearly mediated.” The review’s pattern goes on like this for its duration, as though Powers has been instilled with the phobia that all critics can’t help but have now: will this–will I–be likable? That this defeats the entire purpose of criticism is obviously alarming. Of course, some critics can’t help but be out of step with what they’re critiquing. In another instance of incorrect grammar and reaching non sequiturs intended to sound profound, Powers states, “It’s easy to read the Del Rey’s map of the noir landscape, but just as enlightening to consider how her musical precedents set the stage for the work she’s doing.”

Once more highlighting the fact that Del Rey has more than a strong tendency to “assimilate” her influences into her own work (in addition to appropriate, as Powers calls out with her mention of Del Rey’s chola braids in the video for “Fuck It I Love You”), Powers is saying yet not saying: this album is sweeping in its derivativeness but since we don’t have much else in the way of works of art in the modern era, it’s pretty good. So why doesn’t she just spit that out? She can dress up the review in verbose succors all she wants, but the takeaway remains the same–begging the question: when did critics get so flaccid? The answer being, of course, when their lives started to be threatened on the internet. There is an inherent timidity afoot in the critical world. In addition to the attempt at blending subjectivity with objectivity for a result that never works, consistently comes off as contrived and inauthentic. Which is also what Powers appears to be saying about Del Rey with the very lines that commence the article: “The trash on the Venice boardwalk sparkles like Wet n Wild lip gloss. This is what people forget about Los Angeles beaches: They’re part of the city, inundated with the city’s grit… ‘I’m mostly at the beach!’ Lana Del Rey exclaimed in a recent interview, explaining her cultivated disconnect from the Hollywood pop machine. Reading this, I wonder where she goes and what she does after she unfolds her towel and sets up her umbrella. Does she drive past Malibu to El Matador, where the water is the cleanest but the one Porta-Potty often overflows? Down to Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro, near the aquarium where schoolkids swarm? In her songs she dwells on Venice and Long Beach, two places where the red signs the city uses to warn of excess sewage in the water show up the most.”

If this doesn’t drench with the sentiment, “You’re a sham of a dumb bitch further perpetuating wrong stereotypes of L.A.,” then one doesn’t know what else could. And it isn’t as “cleverly hidden” as Powers would like to believe. Nor is the review as “ultimately positive” as her defenders, mostly critics themselves, would like to pretend. It is, in fact, the worst kind of indictment: one that feigns being “nice” with enough occasional sugar coatings to conceal the crux of the message. But for as stupid as people are, they’re not so stupid as to not read between the lines. Especially Lana Del Rey fans, the last of the intellectuals in their pseudo-intellectualism.

So why don’t we return to the no holds barred nature of what critiquing used to entail? For the purpose of criticism, once upon a time, was to intelligently appraise a piece without faux insightfulness (“We live in a time when the interpretation of dreams has given way to psychopharmaceutical rebalancing, and when the neatening effects of self-actualization are generally considered more rewarding than the dwelling on the psyche’s dark expanse”) interwoven with declarations of being a fan despite certain grievances with an artist’s current work.

And just because Powers parades a sizable amount of knowledge on “Lizzy Grant’s” backstory doesn’t infer that she’s a fan so much as a voracious student of pop culture. This much is evidenced in yet another of her more lambasting paragraphs:

In her early days, what she claimed — bouffanted femme-fatalism weirdly aligned with a tattered Fourth-of-July style patriotic nostalgia, Bettie Page reborn as an Instagram star — felt undeveloped and, because of that, cynical. Intimations that she’d had help in inventing herself clouded her status. But as she built her repertoire, Del Rey proved fully committed to the messy alignments of her art, and better able to articulate how they formed the stories by which she, or the characters she claimed as her own, lived. She would be a problem — a loyalist to outdated ideals like mad love and bad-boy machismo, a constant gardener of the weediest patches of the contemporary psyche. On NFR! she remains that artist, even as she asks herself if she might, with insight, better compartmentalize her impulses.

One would ask the same of a critic these days, so utterly schizophrenic about being transparent with their opinion. And then backpedaling when they wonder why fans or the celebrities themselves got offended. At that rate, it is more worthwhile to not even attempt pandering. Yet that’s what the entire century is built on. Possibly why Del Rey seems so yearning for a return to the twentieth. And why criticism as we once knew it is dead. Shot and killed by the celebrity worshippers who have beaten the fear of their gods into critics.