As the 80s drew to a close, the hangover that was to come as a result of the excess was already brewing. The effects of the stock market crash of 1987 were still being felt with a panic on the part of yuppies that they might never be able to recoup their vast fortunes. Instead, they would have to settle merely for a “normal” fortune. To that end, the psyche of the uber rich (a.k.a. those who control the planet) is tapped into with the utmost relentlessness by John Carpenter in 1988’s They Live. Called a “cult classic” when in fact it should be taken as biblical scripture with not only what it details, but what it prophesies with lines like, “They want benign indifference. We could be pets or food, but all we really are is livestock.” As well as touching on, via allegory, how the relationship between the rich and the government is symbiotic as one of the aliens declares, “By the year 2025, America and the entire planet will be under the protection of this power alliance. The gains have been substantial for us and for you, the human power elite. You have given us the resources we need for our expansion. In return, the per capita income of each of you has grown.”

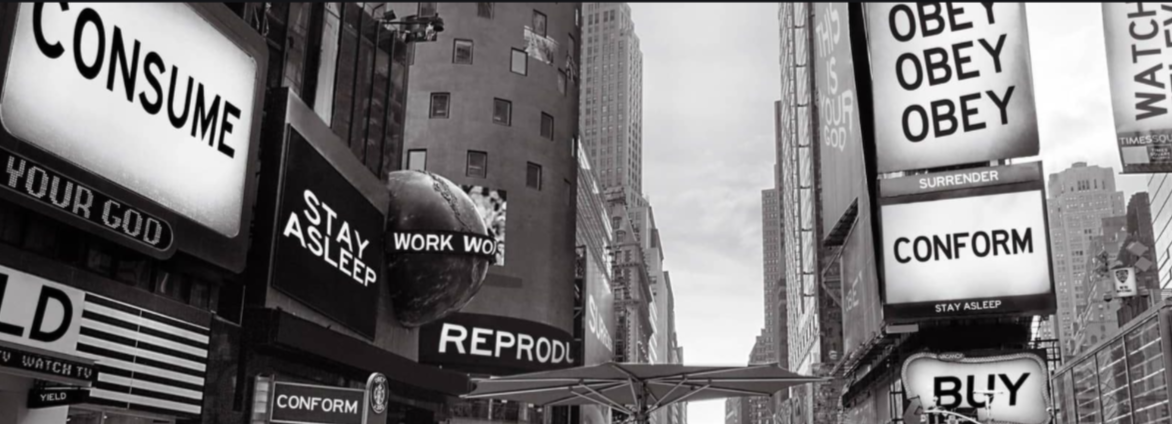

Dubbing this ruthless race that has swooped down upon Earth as “free enterprisers,” They Live unfolds like a combination thriller/action movie with one man’s mission to open the eyes of the rest of the country providing him with a herculean task. In the source material for the film, Ray Nelson’s “Eight O’Clock in the Morning,” they’re instead called “Fascinators.” Regardless, their game remains the same: treat Earth as though it is their version of a Third World country to be plundered of any and all resources and riches before dipping out to colonize another (how very British). Pillage, pillage, pillage until there’s nothing left–and make sure the natives are docile while you do it. Like any hostile takeover, the best way to infiltrate is through subterfuge rather than outright warfare. And the free enterprisers have hypnotism down to a science in order to achieve that tactic, doping up the poverty-stricken masses with ads (back then, it was TV and billboards, now, it’s the internet in every iteration) featuring subliminal messages like, “Obey” (which Shepard Fairey would “borrow” later on), “Marry and Reproduce,” “Consume” and “Stay Asleep.” All designed to keep the slaves–and they (meaning we) are slaves–complacent. Foolishly convinced that if they just “follow the rules” and have faith that, one day, they, too, can benefit from the purported spoils of capitalism, then all of their hard work and suffering will pay off. It won’t. But that’s certainly what a drifter called, fittingly, “Nada” (George Nada in the short story) still believes when he wanders into Los Angeles from Denver, hoping to find some kind of “gainful” employment. Again, this was a movie that came out during a recession year that followed the crash of ‘87. Times were particularly raw.

Thus, it only makes sense that the opening scene would commence at an unemployment office. The most depressing attempt to give human beings hope that their potential might be commodifiable–with the beige walls and fluorescent lighting to drive that point home, along with the mocking sign: JOB OPPORTUNITIES. It is here that The Drifter (Roddy Piper) is met with derision by the woman in a skirt suit clearly getting off on her power. Maybe if he had been able to put on his special sunglasses at the time, he might’ve seen that she was one of them–implemented in the system to ensure that the likes of The Drifter stay subjugated, hopelessly off track in the “land of opportunity” without any opportunity for his “kind.” That is to say, the poor who keep getting poorer because the system is set up to make it that way.

Deciding to carve out a job for himself, The Drifter meanders over to a construction site near a church. After finding work there, he befriends a fellow down on his luck proletariat named Frank Armitage (Keith David)–which also happens to be one of Carpenter’s pen names. It is Frank who seems to have the unavoidableness of the rigged system more figured out than The Drifter with platitudes like, “The Golden Rule: he who has the gold makes the rules” and “The whole deal is some kind of crazy game. The name of the game is: make it through life. Only everyone is out for themselves and looking to do you in. You do what you can, but I’m going to do my best to blow your ass away.” Just a bit of Capitalism 101 with regard to the American encouragement of the “competitive” (read: cutthroat) spirit.

Yet it is soon The Drifter whose knowledge of how the system really works is elevated well above Frank’s. All thanks to the discovery of a box of abandoned sunglasses after the church where the resistance is operating gets raided, the police popping off every last free thinker in the place. As the rest of the movie becomes about The Drifter’s tireless quest to open everyone else’s eyes the way his have been, he is met with an unsurprising amount of aversion to what he’s saying: the truth. A refusal to accept reality (as immortalized in the epic fight scene between him and Frank), however, is something he underestimated in the human condition. People would so much prefer to remain in the numb pleasantness of their coma than to open their eyes and acknowledge just how horrifying their existence really is beneath the surface. In many ways, this aspect of They Live is something of a blueprint for the themes of The Matrix.

When The Drifter finally does manage to break the spell by destroying the hypnotizing signal at the TV station, he dies believing that his demise wasn’t for naught. That he has given humanity the tools they need to now go forward and shake off the binds of the oppressor. And yet, something tells one that The Drifter did, in fact, die in vain if we’re to judge the actions of the public by today’s standards.

After they all wake up, so to speak, a montage of scenes showing people’s horrified reaction to who the ruling class really is ensues before the movie ends with an alien asking the human he’s boning, “What’s the matter, baby?” There is no epilogue showing that the humans went to war or they managed to free themselves from being always within the powerful clutches of the free enterprisers. The reason for this, we find in the present, is because Carpenter likely hoped things wouldn’t be as grim as he internally projected.

With an open-ended conclusion, it gave movie-goers (pinko movie-goers, in the eyes of the Repubs) a chance to believe in possibility for the future, one that wouldn’t have the same unquenchable thirst for money that Reaganomics so encouraged in the 80s. That it wouldn’t be exactly as that free enterpriser said in his speech about their caste taking over all of Earth in this fashion by the year 2025. It didn’t even take that long. All it took was the fall of the Berlin Wall and, with it, the ability of America to shat all over the world with its ultimate free enterprise concept–globalization (just another synonym for homogenization)–because communism had been stamped out. The Earth was “free” again–for unbridled trading opportunities. Pillage, pillage, pillage until there is nothing left.

They Live needed no ending because we as humanity were supposed to write it. And all we did was go back to sleep. Obey, Consume, Conform–repeat. In other words: they live–lavishly and without worry–we sleep, in the mire, constantly worried about our god–money. The end.