A deliberate choice, to be sure, Interpol, now in three-person form without Carlos Dengler on bass (the second album since El Pintor that this has occurred), commences their latest record with “If You Really Love Nothing.” With the corresponding video, it truly makes a grand statement about what it feels like to live in the now, where all we have, more than ever, is the present–this sense of foreboding that everything we have could slip away at any second, so why bother clinging onto anything or anyone?

That the title of their record is Marauder also leaves one pause to consider the origins of the word, which stems from “vagabond” and translates literally in the now to “rascally.” That one can’t perhaps be a vagabond without either already starting out as or becoming a rascal addresses a certain conundrum that this particular century has forced millennials in particular to reconcile with: do we want to bother giving a shit when all evidence points to the fact that everything those who have worked for before us is liable to slip through one’s hands like quicksand? In that case, do we take the track formerly laid out despite knowing it’s off the rails for the sake honoring the time-honored tradition called “civilized” life?

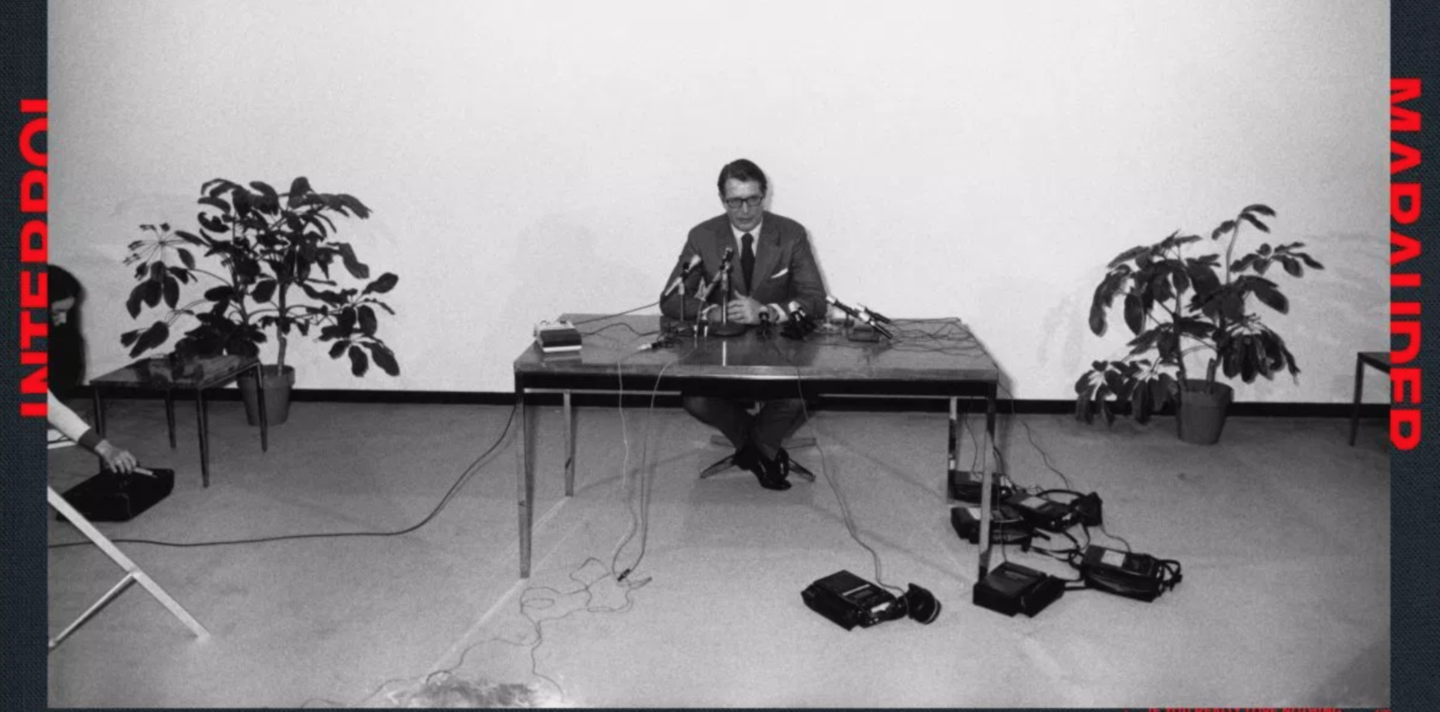

In the persona of the marauder, Banks thinks no, and is at his most honest, tying the definitions of a marauder and a rover (a.k.a. wanderer–someone who can never stay fixed in one place) together once again on the first single, “The Rover,” by singing, “‘Walk in on your own feet,’ says the rover/’It’s my way or they all leave.'” A faint allusion to the very man who made the cut for Marauder‘s cover art, Elliot Richardson (the U.S. Attorney General who refused to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox when Nixon told him to during the Watergate scandal), Banks urges his listeners to realize, “You can’t stick to the highways, it’s suicide.”

On “Complications”–the second most useful word for describing this century after “marauder,” Banks addresses the later issues that come with being a free spirit, seen so often as “having it easy” for not being fully connected to anything or anyone, not realizing that, for the constant rover, the dilemma is, “Oh, what’ll it be?/It goes on and on/On the street, hey/It’s like a blindness”–one that can never be shaken in the endless quest for a place to “be.”

Addressing the benefits of being in a state of constant homelessness, “Flight of Fancy” finds Banks in his marauder mask declaring, “This is make believe/Like sleight of hand/And a custom vagrancy of mind/Well, I demand it/It’s just my agency/My flight of fancy.” That Banks acknowledges there is no being with more agency on this earth than the rogue who chooses not to follow a path merely because it is expected or over a fear of judgment from the herd if he does not again coincides with the definition of a marauder–someone who raids or plunders, except in this case, it is raiding the very core of “the system.”

The tongue-in-cheekly named “Stay in Touch” (which feels like an ironic nod to all the ways in which we’re now capable of remaining in contact and yet, ghosting is more of a phenomenon than ever–especially on the part of marauding men), Banks unravels the tale of a man who briefly makes a connection with a woman, rehashing, “When we first met you were love tied/Faith like a tree and laying roots/He could see you as his wife then/Honestly I could see it too/Then he became my close friend/We spoke of his love for you often/I came to see you in starlight/And let electric fields yield to skin.” Poetry aside, the story is told with a foreboding sense not just in syntactical structure, but also in terms of this reality that a marauder (or, rather, most modern folk), almost gets off on causing destruction, on sociologically studying how it affects those he harms emotionally around him for use, perhaps, at a later date. As Banks puts it, “That’s how you make a ghost/Watch how you break things you learn the most/Something about the one that negates hope/Marauder chained of no real code/Marauder breaks bonds.” So, it would seem, one must in order to survive in this century–particularly when to have friends and relationships really just means god (i.e. the government) can keep tabs on you all the more. For themes of being watched–constant surveillance–also pervade the narrative of the record.

Building on the commonly held belief that technology has become the new god, Banks vaguely comforts with the notion that, yes, Big Brother is very much watching. He–technology–is the thing that will now hold you accountable for your actions from a moral standpoint. As Banks stated in an interview with NYLON:

On a song like ‘Surveillance,’ it’s not quite so dystopian so much so as I got fixated on this idea that if we can go back and find a termite in amber that’s three million years old and we can find out what it ate for lunch now… With all this data, artifacts of what our phones are recording and what satellites are recording and what CCTV is recording, in two million years, I feel like your ancestors are going to be able to flip through your life like a book. Even moments when you thought you were alone. I feel like if we can piece together that, they might be able to reconstruct even moments where you thought you were alone of August 13 of 2003 and just sort of watch your life. What that kind of means to me, is that it’s sort of like someone actually is able to see everything that you did and theoretically pass judgment on you. That’s basically our concept of what God is… It’s someone that can hold you accountable for everything that you did.

With this in mind, a not so latent desire for a return to a more primeval state is understandable, with Banks painting the image of the untrackable life on “Mountain Child.” Looking to what sounds like a whimsical nymph for inspiration on how to live, Banks is awestruck of a natural state of being as he asks, “Are you out of your head?/Why you out of my bed now?/Mountain child you are my queen in white/Won’t you come along with me/Show me what it is/What you use it for/I’ve seen you so high like a meteor.”

Interpol’s nature motif remains something to strive for in “Nysmaw,” where, once again, the marauder is reluctant to make any concrete decisions, least of all ones that will result in permanence, cautiously inquiring, “Is it safe, are we far for the mountains?/We walk through the trees,” in between reminding, “Oh, aimless sharks don’t react to soft attentions/They know how to wait.” In other words, never let a pretty face distract you from your own iconoclast’s path.

After Banks reminds us that, with our narcissistic use of social media, “We are leaving something frame by frame” on “Surveillance,” the lazily titled “Number 10” explores the ultimate cliche: an office romance. Somewhat out of place thematically (for what marauder could possibly hold down an office job?), the narrator describes an illicit affair with a supervisor named Ella that is made all the more aggravating by her position of authority over him, prompting him to snap, “I don’t know what week it’s under” and “Go and talk to Steve about it.” In other words, this sounds to be the cautionary story about the negative effects of staying in one job, if for nothing else than to have to give both body and remaining soul to the boss.

Appropriately, then, this follows up with “Party’s Over.” Again addressing the ominous motif of surveillance, Interpol gets at their most Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino with the common addiction to “popping pills and masturbating to Instagram” (figuratively and literally) as he croons, “I can see you on internet/That’s your milieu/Practically you are intimate/Suds in the tub/I keep up with your interests/Who’s that beside you making the cut?”

A dig at the selfishness and masturbatory qualities of these mediums with which we have become fixated on, “Party’s Over” is one of the most lyrically disturbing offerings on Marauder, with a petite “Interlude 2” to give us pause on what to do with our non-committal voyeurism.

That Interpol ends the album with a title, “It Probably Matters,” in direct contrast to its first track, infers that even the marauder must admit from time to time that there is meaning. Moments when we must admit that this may not be a random coincidence–our existence here. The thing is, only the sadist watching us from above can tell us why, and he simply won’t (he is definitely a man, after all, for who else could be so cruel?). It’s just his “flight of fancy” to transform humanity into ruthless marauders over enough of a period that teaches them that to care would be the criminality.