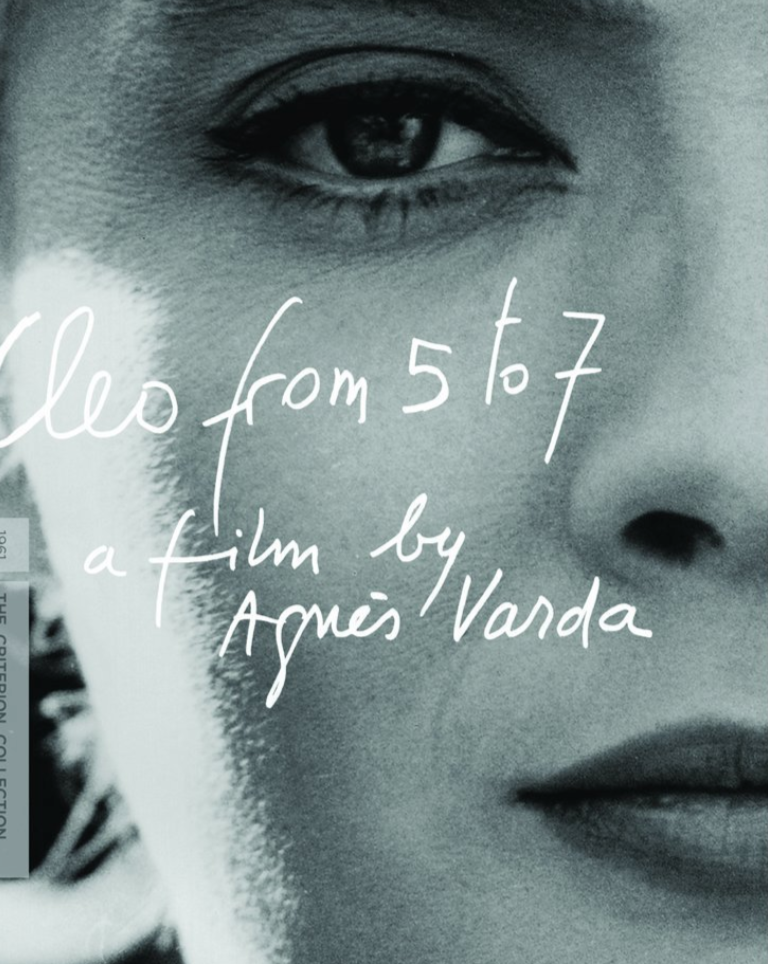

While Agnès Varda might not have been a vain or decidedly frivolous woman, the manner in which she fell prey to death harkens back to one of her most well-known movie characters, Cléo Victoire (Corinne Marchand), in the beloved beacon of early French New Wave cinema, Cléo from 5 to 7. Although Cléo is beautiful and has a relatively successful singing career, the dark shadow potentially case by the reaper above her won’t go away, nor is it remedied by seeing a fortune teller at the outset of the movie, one who confirms all her worst fears about waiting for some potentially fatal test results from her doctor.

Distraught at first over the reading, Cléo insists to herself that “as long as I’m beautiful, I’m alive,” because “ugliness is a kind of death” so how can she be suffering from it if she’s not aesthetically hideous? Even so, she is aware that if she is dying, it’s only the inside that will matter now–not from a personality or “good person” standpoint, but in terms of it affecting whether or not her demise is imminent. To that former notion, however, Cléo suddenly becomes hyperconscious of the vacuity of her life. Buying hats, lounging around, cursing men. What does it all mean? And what can she do to go on preserving that vacuous little life? Thus, she tells her maid, Angèle (Dominique Davray) that she’ll kill herself if it turns out to be cancer. Angèle does little to comfort her, noting that “men hate illness” and that Cléo ought not to wear a new hat on Tuesday as it’s bad luck.

While Varda continued to show her incredible influence over cinema–particularly in the realm of documentary film in her later years (namely Visages Villages, far more charming in its Frenchness than Amélie)–any discussion of having cancer was never made mention of. As though taking a page from her own reluctantly brave character, Varda never addressed the subject, something that, incidentally would have been rife for discussion in one of her movies, particularly as a feminist filmmaker suffering from breast cancer. And yet, maybe it was the same phenomenon that had occurred with Nora Ephron, the woman who famously used “Everything is copy” for her creative inspiration, but couldn’t bring herself to wield that mantra in a frank discussion about being diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia in 2006. She kept that to herself until the very end, proving perhaps that the things that affect us the most are things we can’t really talk about, no matter how theoretically cathartic. Irony once more factoring into the idea that both of these women had endless resources to exorcise their fear of the end.

So, too, did Cléo, a singer who bemoans wanting to project more poignant lyrics but then grows filled with melancholy as she sings a new composition filled with too much death imagery to bear. She wants to remain as she always has been in order to survive, to feel somewhat happy: at the surface of things. Unfortunately, like Marilyn Monroe before her, the woman endlessly preoccupied with her image and looks ends up driving any potential for real and meaningful love away. And as we all know, especially Narcissus, a reflection can’t reciprocate anything, nor love or hate you as much as you do it. Cléo’s childlike maturity, is, in fact, directly related to her self-obsession. In being faced with the reality that her death is imminent, however, she is forced to come to grips with certain truths both about herself and existence that she never would have otherwise. Varda, luckily, already seemed to have all the answers to the mysteries of life long ago. No cancer needed.

Contrarily, for most (Cléo included), life only becomes precious when it’s in peril. But for Varda, it always was, which is, in part, why talk of her cancer–her signed, sealed, soon to be delivered death–did not interest her. Because death, as Cléo said, is a form of ugliness that Varda didn’t address in her work. At least not with crassness. And yet somehow, Jean-Luc Godard still lives. That cold bastard just proving that to be unfeeling is to live longer. See Villages Visages (which you already should have by now) and you’ll understand.