The evolution of Candyman into its current 2021 state might be surprising in some ways to those familiar with its origins. For the genesis of the racially charged tale stemmed from a short story called “The Forbidden” by Clive Barker from his multi-volume series, Books of Blood. And being that Barker (if his first name wasn’t enough of an indication) is British, the original setting took place on a council estate in Liverpool. It was Candyman’s first director, Bernard Rose (also a Brit), who decided to move Candyman, de facto Helen, into the world of inner-city Chicago. And, as Rose stated himself, “The Candyman is not Black in [Barker’s] story. In fact, the whole back story of the interracial love affair that went wrong is not in the book. Everything that’s in the book is in the film, but it’s been amplified.”

What’s more, with Virginia Madsen (herself a Chicago girl) cast in the role of Helen Lyle, the perfect virginal, Aryan cliche was created with her image. The one necessary to both adhere to and subvert the white savior trope that would become apparent from the outset of the film’s narrative.

Commencing with overhead shots of Chicago that have since become iconic (not only for preserving a moment in the city’s history, but for playing up near-Hitchcockian semiotics), 1992’s Candyman eventually transitions to a scene of Helen, a grad student doing her thesis on urban legends, in a classroom listening to and recording someone rehashing a bit of Candyman lore. Doing the research in collaboration with friend and fellow student, Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons), the duo finds themselves drawn to the very source of all things Candyman: Cabrini-Green. Although some unfamiliar with Chicago history might assume the housing project is merely a “made up” name for the purposes of cinematic glory, Cabrini-Green was very much a real place. In fact, the Chicago Housing Authority’s mid-twentieth century attempt at “urban renewal” became a quintessential example of all that was (and is) wrong with America.

Although Cabrini-Green started out as “rowhouses and extensions” under the Francis Cabrini moniker primarily dominated by an Italian population, it ultimately became an overcrowded, crime-ridden project where low-income Black tenants were piled on top of each other (at its zenith [or nadir, depending on one’s perspective], Cabrini-Green housed 15,000 people). Relegated to some cordoned-off state of existence that Helen calls out to Bernadette in remarking upon how her own condo was initially intended as a CHA project before developers realized that wouldn’t “quarantine” the poor folk enough from the rest of the “mainland” city.

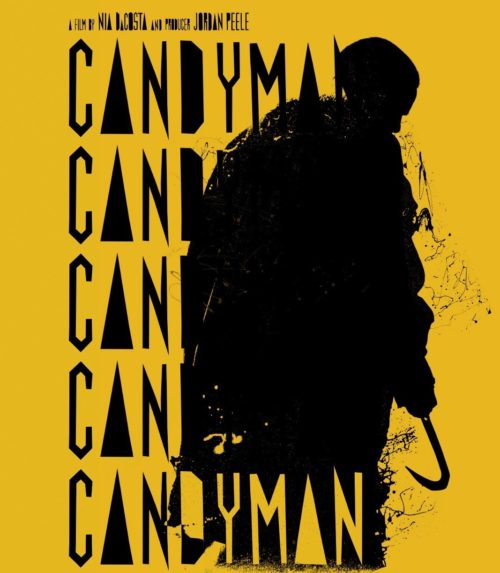

Being that Cabrini-Green still very much existed at full capacity in 1992 (the final teardown wouldn’t happen until 2011), Rose perhaps missed a greater opportunity to make a comment on racial and socioeconomic disparity at the same level as Nia DaCosta (who co-wrote the sequel-ish movie with Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld), this being her sophomore film following the critically acclaimed Little Woods. Plus, with Peele’s rapier-sharp knack for critiquing the white hypocrisy that abounds in relation to Black culture, Candyman was due, in many ways, for a revisit and refresh. One that emphasizes the “icky” problem of gentrification, how even broke asses (a.k.a. “artists”) and people of color become part of its vicious cycle.

In 1992, Helen is capable of acknowledging the issue by telling Bernadette, “My apartment was built as a housing project. Now take a look at this. Once built, the city saw there was no barrier from here to the Gold Coast. Unlike where the highway and the El train keep the ghetto cut off. So they made minor alterations. They covered the cinder block in plaster and sold the lot as condos.” In 2019 (the pre-pandemic year the new version is meant to take place), Cabrini-Green is no longer off limits at all to a pair of yuppies like visual artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) and gallery director Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris). For the couple has chosen to make themselves right at home in one of the converted condos that sprung up there, already begging the question of how complicit people of color are in occasionally benefitting from their own collective historical trauma. It’s Brianna’s brother, Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett), who reminds Anthony and Brianna of how fucked it is for them to live in an area (and apartment) as haunted as Cabrini-Green. Not just haunted by the unhealed wounds of Black subjugation, but, obviously, Candyman. Himself a very metonym for Black oppression.

Yet it isn’t the story of Candyman that Troy focuses in on as much as the Helen Lyle aspect of it, proving, once again, that even an urban legend about a Black man has somehow managed to get gentrified by a white person, adding a poetic layer of depth to this version. As Troy recites the lurid tale of how Helen became “obsessed” by Candyman and Cabrini-Green while working on her thesis, he also reminds that she beheaded a Rottweiler and stole the baby of a young woman living in the project. Using the storytelling device of shadow puppetry (courtesy of the Chicago-based company Manual Cinema) to eerily show these flashbacks, the method is also wielded at the beginning of Candyman when a boy named Billy Burke (Colman Domingo) living in Cabrini-Green in 1977 uses his own shadow puppets on the wall to tell the all-too-common story of a cop stopping a Black boy for no reason… other than the sheer joy they get out of harassment.

Burke’s shadow puppet narrative is interrupted by his mother calling out to him to do the laundry. Vexed, he nonetheless takes the bag over to the basement in compliance. On the way, a police car lying in wait to capture the Candyman gives Burke (a name itself that possibly pays deliberate homage to the last name of Helen’s psychiatrist in the first Candyman) the creeps. But not as much as he gets them when alone in the basement. A hole in the wall near the entrance to the laundry room provides Candyman with the chance to toss a piece at Burke. When he emerges, ghoulish and horrifying, Burke remains frozen until he comprehends Candyman means him no harm (at least not this time). But it’s already too late: Burke has let out a shriek loud enough for the police to hear, and they come descending upon Candyman like a swarm of bees (yes, one of the key talismans of the legend).

In Rose’s version, there is only the brief visual suggestion that Candyman puts razorblades in the candy he passes out to kids (a bag of it discovered by Helen in his lair). In DaCosta’s, she more fully develops the concept by adding in that Candyman was wrongly accused of being the guilty party responsible for lacing sweets with blades when a white girl was on the receiving end of one of those lethal pieces of candy. As Burke tells Anthony in the present day, after Candyman was brutally beaten by the police and arrested for the crime, the razorblades still appeared in candy even afterward, proving he was innocent.

And yet, considering the genesis of how Candyman came to be, his continued martyrdom and unjust huntedness is no shock. For he began as Daniel Robitaille, a Black painter of noble status in the nineteenth century who inevitably fell prey to the terrors only white men know how to unleash, pursuing him after the father of a wealthy white woman (whom Robitaille was hired to paint) learns of their tryst, as well as, worse still, his daughter’s pregnancy. Thus, he instructs a band of men to retaliate. And, oh, how they oblige. Mutilating him, severing his hand and replacing it with a hook and then, for the pièce de resistance (since white men have, in their minds, elevated violence to an art), unleashing a swarm of bees from a nearby apiary and smearing his body with a honeycomb.

Despite the fate that befell him as a direct result of getting involved with a white woman, Robitaille remains fixated on finding his way back to the woman he loves. Thus, 1992’s Candyman is, in so many senses, all about a white lady: Helen—as manifest in the famous line, “It was always you, Helen.” Her initially easy infiltration into Cabrini-Green without any fear of violence against her (in real life, in fact, Rose had to pay off some gang members to leave them alone during the filming) speaks to the naïveté of the white person in general and the white savior in particular. Especially when it comes to believing they can remake an entire race or geographical location (often inextricably linked) in their image. As though they should be treated like a motherfucking god. But Candyman is here to change that perspective, himself almost godlike in his ability to be everywhere at once—the benefit of manipulating a hive mind. Indeed, it is only the faith of his “congregation” that keeps him alive (literally and metaphorically) and, in turn, those who willfully disbelieve in him, like Helen (at first), incite him to appear before them and kill. Unless, of course, Candyman gets off on a bit of stalking and mind control before finally ending the life in question. And yes, Helen is so much fun to hypnotize as he makes others believe she’s responsible for a rash of murders.

This is where the shadow puppetry comes in during DaCosta’s Candyman, with Troy describing how, as everyone searched high and low for the baby, Helen seemed to disappear, reemerging the night of a bonfire to, as the residents of Cabrini-Green learn, save the child from Candyman’s clutches, understanding only after she’s dead that she was possessed by Candyman’s powers. This, to be sure, treads on the dangerous stereotype of vilifying the Black man as usual, but the line is so gently toed as to remain effective for the purpose of rendering Candyman into something like a Black Dracula. In this bonfire denouement, as well, Candyman becomes that rare breed of a white savior story that actually forces the white person to die, to be martyred for what they usually only claim they’re willing to die for (see: Michelle Pfeiffer as LouAnne Johnson in Dangerous Minds or Hilary Swank as Erin Gruwell in Freedom Writers—both real-life white lady teachers who ended up profiting financially from the inner-city kids they were meant to have so “selflessly” helped).

By the end of DaCosta’s Candyman, however, a spiritual reversal of gentrification has transpired where a physical one cannot. For the story of Helen has been cast out entirely, eclipsed by a divorced narrative. Therefore, Helen is no longer relevant to the Candyman of the present. The one born of a trauma completely separate from losing the white woman he once loved. The new Candyman does not love a white woman, instead mourning the loss of his relationship with a Black one. This, as a result, opens the door for subsequent films in the Candyman franchise to eradicate all traces of the gentrification that Helen inflicted upon the legend. Thus, a Black story originally told by a white person has been “given back” to who it really belongs to. Naturally, this could invariably be cocked up again with the wrong director and writer.