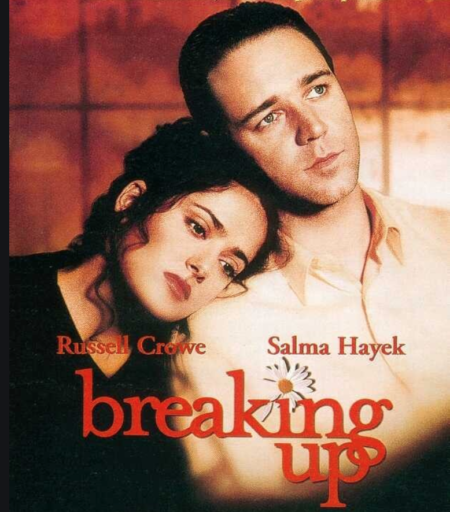

There was perhaps something in the air in the Manhattan of the late 90s. Something that made it so that women who oughtn’t settle for such patent douchebags decided to do just that. Although Sarah Jessica Parker as Carrie Bradshaw would burst onto the scene to exemplify this on June 6, 1998, before she brought the trope into mainstream consciousness there was Salma Hayek as Monica in 1997’s Breaking Up. Directed by Robert Greenwald (perhaps most infamously known for directing Xanadu) and written by Michael Cristofer, the film’s often play-like qualities stem from the fact that Cristofer is adapting it from his own of the same name. Yet within the context of late 90s New York, nothing about this feels out of place or clunky. Of course, it could never be released now, as audiences have little patience for long stretches of dialogue or repartee–particularly when most people would never spend so much time drawing out a breakup through heated arguments when they could just pull out the stock “It’s cancelled” line and move on quickly to the next person without much thought for the last.

In Steve (Russell Crowe) and Monica’s case, however, this would be unthinkable. For not only do both of them seem to get off on their anger toward one another (which, in turn, leads to the most addictive type of sex), but they have also both put too much time into the relationship (two and a half years) to pull their chips off the table in the game of roulette called love. And, it’s true, they do love each other. At least by standards of what the twentieth century displayed and promoted: that the more toxic a relationship, the more it meant you were truly amoureux de quelqu’un. That it was a great love by the fraught precedents set by some of the most whirlwind romances in classic literature. Yet what the common person failed to take into account was that these stories were written for the purpose of entertainment. That in real life, to carry on in this fashion would amount to never getting anything done. And it feels as though Steve and Monica rarely do; though he’s a photographer (primarily of fruits, especially bananas, for an overt psychological layer) and she’s a teacher, these things always come second to whatever state the relationship is in–swinging like a pendulum between the spectrums of heated passion and heated rage. A fine line between the two never easily toed by Steve and Monica as they spend most of their moments together ranting, raving and then fucking. Though there is an occasional moment of tenderness. Like when Steve cops to his fuckboy behavior (of course, at the time, this all-encompassing term for most men in New York wasn’t around) in trying to slink away in the middle of the night by explaining, “I don’t know who I am here. I get lost here.” Monica asks, “Is that such a bad thing?” He replies, “It’s not that it’s bad. It’s not that it’s good or bad, it just takes over. It changes everything.” Increasingly frustrated, she insists, “It’s supposed to change everything, Steve.” Skeptically, he returns, “Yeah. Love, right? But suppose it doesn’t last. I gotta hang on to what I have besides this and who I am away from this. Because if this isn’t gonna last and this is all I have and it doesn’t last, who am I?” She urges him to dig deeper into the truth by demanding, “What are you so afraid of right now?” He finally admits, “I’m afraid that I won’t ever love anybody as much as I love you.”

His intense fear of losing someone he loves so much fills his brain with illogical coping mechanisms, a flight or fight response that crops up every time he feels as though they’re getting too close. It bears noting that Robert Greenwald’s father was esteemed psychotherapist Harold Greenwald (writer of The Call Girl: A Social and Analytic Study)–a piece of trivia that seems to play into the neurotic behavior that occurs as a result of being in love throughout the film. Particularly when Freud himself appears to Steve in a dream of his wedding to Monica. This in addition to Karl Marx and Albert Einstein, two thinkers Monica had also referred to as she packed up her things to move in with Steve before getting married. Alas, this series of nightmares causes Steve to conflate dream with reality at the actual wedding, asking Monica, “This is not a dream?” Upon confirming it’s not, he passes out. But unlike, Carrie’s Mr. Big (Chris Noth), at least he showed up in the first place. Though he might have been better off not bothering. The similarities between this set of duos almost appears to rear its head again when it looks as though Monica might still take him back even after his inability to go through with the wedding, like Big, citing that the ceremony has nothing to do with other people, that it should have just been about them.

At one point, before Steve came to her during a longer breakup period to suggest they get married because he didn’t want to bother trying to rebuild what he already had with her with another woman, Monica was the one who seemingly assessed their situation with modern pragmatism: “There used to be reasons for people to be together. To stay together. Like stability and security and even kids. But you see, I don’t need you for these reasons nowadays. I mean I can get all this on my own if I wanted to. So if there are no real reasons for two people to be together, then you’re into unreal reasons. Fantastic things, like happiness, good company and comfort and understanding and emotional support. God, you wouldn’t ask that much from a saint. So you look at this person that you’re having a relationship and you think, ‘What is he good for anyway?’” She then pulls that about-face trick that occurs throughout the movie by negating all that she’s said with: “I hate being without you.”

Yet, like the U2 song overly romanticized in the mid-90s thanks to Friends, it seems they can’t live with or without each other, ultimately leading to this constant state of flux between them that prevents both from enjoying the moment within their relationship or moving on.

Then again, another long-held theory about love would suggest that precisely because they were so genuinely in love with one another, they had to destroy it, for “true love” as it is written in Great Expectations can only cause madness and suffering. Whereas “practical” love is what enables most people to survive their day-to-day. So it is that, despite his constant calls, once Monica finds another apartment, he’s forced to stop dialing (oh the gloriousness of the 90s when stalker behavior could be prevented as simply as an address change).

Yet even though she knows their dynamic consistently ends in tears, she can’t stop thinking about him, ruing to her therapist (for both of them are telling this story of the past to their therapists in the present), “If I could only go through just one day without having his name go through my head.” But does that mean it was real love? Or is it the hangup humans have when a failure of this nature occurs that makes them dwell on it for years afterward? As Monica describes it, “I never really found out what was wrong with us. There was never a real problem, there was never anything you could put your finger on.” Further adding, “You have this experience of feeling something so strong, so good. And as bad as it gets, you can’t forget that. And you always think that tomorrow it will be the way it was in the beginning. And the memory gets stronger and stronger and it just makes every day worse and worse.”

When even more time has passed and the two run into one another in Santa Barbara (for yes, shades of Before Sunset also permeate the film), it seems the problem between them wasn’t that love wasn’t enough, but that they had met at a period in their lives when they weren’t ready for one another. To take the “maturity plunge” required by commitment. Maybe if they had met just a few years later, it all could have played out differently. But, of course, playing the game of “what if” will drive anyone crazy. Concluding with a title card that reads “The End… (maybe)” infers once more that when it comes to a great love that failed, it’s impossible for many to ever truly move on. Is it the nostalgia that plays with your mind or was that feeling real?

And as the credits roll to the sound of people telling their worst breakup stories (building on the “man on street” interview segments of the movie that also remind one of Sex and the City’s first season), the film iterates that while “solid” love of the non-toxic twenty-first century variety is best, one can’t help but continue to dwell twentieth centurily on what might have been with the one who exemplified the fiery line between love and hate.