As everyone continues to praise Lady Gaga for her horrendous accent in House of Gucci, there’s something else in her performance that audiences have unwittingly lauded: a villain. While it’s nothing new for villains to get a “closer look” in the present marketplace (see: Joker, Cruella), what Ridley Scott’s movie doesn’t much bother with is trying to humanize Reggiani in any meaningful way, instead opting to boost up the caricature factor to amplify Reggiani’s brand of psycho (therefore the potential for audiences to parrot back phrases like, “Father, son and House of Gucci”).

This was once the case with Betty Broderick, who murdered her husband herself (unlike Reggiani, who couldn’t be bothered to get her hands dirty) in 1989, before the Netflix series Dirty John got a hold of the narrative and called it The Betty Broderick Story. It no longer had anything to do with being Dan Broderick’s story (which he was able to make the loudest in divorce court), but what he did to drive Betty over the edge… and, mind you, he did so via the level of manipulation that makes Maurizio Gucci seem like an angel. In House of Gucci, no such attempt is made at rendering Patrizia as a more “empathetic” character. No scenes devoted to revealing Maurizio’s degradation or verbal abuse toward his wife as was the case with Dan and Betty.

What’s more, where Betty has expressed a lack of premeditation and frequent remorse for her actions as time went on (though not enough to make the jury think so at the time of her second trial), Patrizia has consistently stated she did nothing wrong. As a result, she has, unlike Betty, no contact with her children, who have rightfully shunned her. And so, while both women were propelled toward the same act for very similar reasons (feeling cast aside, ignored and unappreciated for everything they had done to help mold their husbands into what they were), it was Patrizia who stayed down a more depraved rabbit hole, not even bothering to at least feign compunction for the sake of somewhat salvaging her public image.

Both recent media portrayals also allude to each woman’s materialistic nature, possessing a thirst for money and clout that ultimately turned both of their husbands off to them. Apart from the fact that they were inevitably going to pivot toward “softer,” more “uplifting” women (in Maurizio’s case, he stayed far more age-appropriate than Dan).

While Maurizio’s background is rooted in “dynasty” (as is typical of European class), Dan’s was rooted in the beloved perpetuation of the “American dream” as he clawed his way through med school and then law school to become the dreaded mutant strain of lawyer specializing in medical malpractice. Maurizio, too, dabbled in studying law before surrendering to the Bob Dylan lyric, “But I’m helpless, like a rich man’s child.” And so, he leaned in a bit more to the family business as his own father, Rodolfo, was about to die. A power shift that made Maurizio’s uncle, Aldo, even more embittered about being the one to put all the work into making Gucci the international success it had become, only for Maurizio to come along and inherit the fifty percent of the business that Rodolfo hadn’t sweated for in the same way as Aldo.

And Patrizia, despite what she may have believed about herself and her “contributions,” certainly didn’t sweat for it either (excluding her fuck sessions with Maurizio). Betty, on the other hand, really did pour her entire being into not only the marriage, but financially sustaining her and Dan as he yukked it up in grad school, leaving her behind to deal with their increasing litter of children (including one that she miscarried, with no emotional support or comfort from Dan) while he attended whatever social engagement he wanted to in the name of “working hard.”

When their income finally started to pick up as the 80s dawned, Betty would bring up what a long way they had come since their starving days in New York—a reminder Dan would shut down as though he didn’t want to think about that lengthy period in his life when they were getting by on Betty’s odd job income alone. Because that would mean he wasn’t totally “self-made,” and that was the image of himself he needed to uphold in order to transcend into the full-fledged douchebag extraordinaire in charge of running the San Diego County Bar Association.

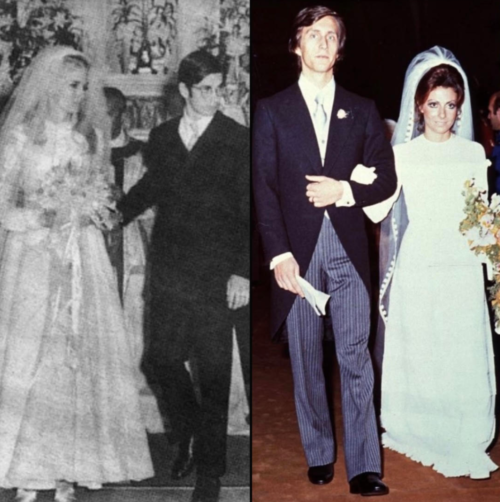

Maurizio, too, started to grow fonder of the “flash” that came with being a Gucci. Especially a Gucci who ended up controlling a majority stake in the company. But long before this, he was still meek, mild-mannered Maurizio. Dan, in contrast, was always some version of an egotistical abuser. The circumstances surrounding each marriage were culturally divergent, and yet, because each couple was ensconced in a Catholic upbringing, the marriage became like an immediate prison, with the religion, as most know, being firmly against divorce (particularly during this era). Betty felt especially regretful of her choice as it didn’t take long for Dan to reveal his possessive and irascible nature in even more full effect than when they were dating.

While Patrizia spent her post-separation days plotting her husband’s death through a pair of hitmen “recommended” by her close friend, Pina, Betty maintained that her actions were more the result of reaching a breaking point on being pushed around and made to feel insignificant by her ex-husband. As Betty stated in her 2015 book, Telling on Myself, “…in a few seconds, I let every pain, every cruelty, every sadness, every hurt and every abuse take me over. It only took a few seconds to define me.”

In short, Betty let that sense of carnal rage finally take hold the way it was begging to ever since their marriage began. Patrizia, despite her own notorious temper flare-ups, was colder and more calculated in orchestrating things. But, at the very least, she spared Maurizio’s new significant other, Paola Franchi, from death, which, in this sense, perhaps makes her the more “sympathetic” person when compared to Betty.

At the time of Dan and his new wife Linda’s murder, American culture was, obviously, more steeped in misogyny than it is now, with headlines (some of which rooted the event in the pop culture of the day by likening it to a “reverse Fatal Attraction” scenario) and news reports quick to easily bill Betty as all-out “crazy” without delving deeper into her psychology—or the “why” of how she reached such an extreme state. With the occasional “vindication” of these women who were so vilified in the tabloid journalism of the 80s and 90s (e.g. Monica Lewinsky, who has gotten her own post-#MeToo say about her situation with American Crime Story: Impeachment), Betty’s story has been revisited with a lens that is more appraising of Dan’s cruel behavior throughout their entire marriage. And yes, like Maurizio, he decided to just up and leave one day without warning, a maneuver that set Patrizia and Betty alike on a descent into madness.

For both murderesses, in the end, it seemed less about money and more about being devalued and discarded themselves by the men they had given their all to. Only to be brutally informed that their effort and devotion was worth nothing.