As Billie Eilish has come forward as one of many “white allies” to speak out among the reignition of the Black Lives Matter movement, her recent interview with GQ for the July/August issue has reiterated what Tyler, the Creator stated after his 2020 Grammy win for Igor: “It sucks that whenever we—and I mean guys that look like me—do anything that’s genre-bending, they always put it in a ‘rap’ or ‘urban’ category. [It’s just another] politically correct way to say the n-word.” Eilish echoed his sentiments, stating that she doesn’t see herself as even remotely “pop,” yet because she’s a teenage white girl, that’s where her music gets placed, as though resting on the laurels of what Britney Spears did twenty years ago (having only ever won in the category of Best Dance Recording for “Toxic”). But just because one teenage white girl is pop doesn’t mean that another is. The same goes for the ways in which “black” music has consistently been relegated to the classifications of “rap,” “hip hop” or “R&B.”

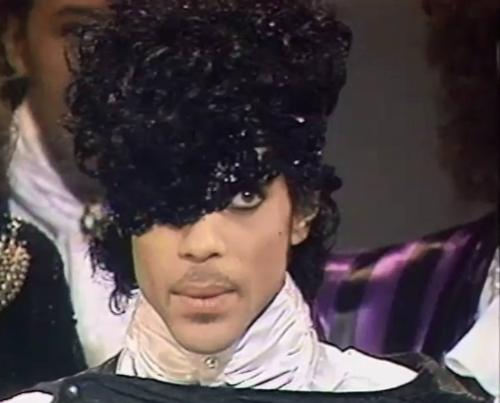

Eilish would go on to add, “Don’t judge an artist off the way someone looks or the way someone dresses. Wasn’t Lizzo in the Best R&B category that night? I mean, she’s more pop than I am. Look, if I wasn’t white I would probably be in ‘rap.’ Why? They just judge from what you look like and what they know. I think that is weird. The world wants to put you into a box; I’ve had it my whole career. Just because I am a white teenage female I am pop. Where am I pop? What part of my music sounds like pop?” And what part of Prince’s genre-bending Purple Rain was full-stop “black”? Only the 1985 American Music Awards can answer the logic behind this thinking, as it was still, evidently, a time when the voters and organizers of the awards (originally helmed by Dick Clark as a network defense against the Grammys moving from ABC to CBS) saw fit to identify any music from a black artist as “black music.”

In a 1985 issue of Jet magazine, one finds it especially ironic that the listing of his awards consists of describing him as a “punk rocker”–a term, particularly at that time, decidedly reserved for white men (primarily British). “Favorite Black Male Vocalist,” “Favorite Black Single,” “Favorite Black Album,” “Favorite Black Male Video Artist” and “Favorite Black Video Single” being five of the ten categories he was placed in. Yet the other five were merely the same except billed in the “pop/rock” sector. Yes, unnecessarily divisive indeed. A Jim Crow level of separatism at a 1980s awards show. And no, it doesn’t seem exactly clear when the American Music Awards saw fit to dispense with these labels of “blackness” (maybe it was after Michael Jackson went full-tilt white, because he was still nominated in the black categories along with Prince and Lionel Richie at this point). Perhaps it’s a part of their history they would prefer to keep nebulous, the same way the music biz doesn’t want to address in too much detail the payola phenomenon that secured ample dominance for white artists to be played on the radio.

Whatever year the AMAs rebranded the names of their categories, they never should have dubbed any type of music as “black” to begin with. This has been so much of the problem in terms of intensifying a sense of black people as “the other,” in addition to forcing musical artists to be backed into a corner for what they can and can’t record, what will and what will not be profitable for their image, therefore a record label. It’s truly a wonder Darius Rucker was ever allowed to front Hootie and the Blowfish.

Perhaps Prince felt just as insulted by the “box-in” as his acceptance of the awards (of which he made a sweep) were, by and large, either a terse thank you or simply letting other members of the band (not all black) speak instead. At the same time, it was likely precisely because the AMAs had carved out a “space for black music” among their “regular” categories that black people were “allowed” to win at all. After all, consider that the Grammys, incepted in 1959, made no “provisions” for the inclusion of black artists, despite the fact that musicians such as Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Fats Domino were extremely popular at the time. Regardless, it was not until 1973 that the Grammys awarded a black artist for Best Record–specifically Roberta Flack for her rendition of “The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face.” Prior to that, the only wins for black artists were in the “rhythm and blues” category, which wasn’t even created as an award by the Grammys until 1967.

In 1989, the Grammys seemed to do their best to “make room” for black performers the way the AMAs already had in their own Jim Crow way by setting aside four rap categories. It should be noted that a considerable portion of awards since the inauguration of these four categories have gone to Eminem. Yes, a white man–so even in relegating black musicians to rap, the Recording Academy still saw fit to rob them in its own insidious way.

As more sweeping systemic changes are made over the course of the next few years, one can only hope that, along with those, the music industry can start to understand that pigeonholing musicians by their skin tone isn’t the best approach to giving out awards. So yes, maybe one day Billie Eilish can be deemed “rap” or Tyler, the Creator can be “pop/rock meets neo-soul and hip hop” instead of simply “urban.” Or maybe classification can be done away with entirely, awards passed out to the crowd like t-shirts shot out of a gun at some corporate-sponsored rally or sporting event (back when such things were merely damaging to mental health instead of physical health, to boot).