An impressive feat in moviemaking alone for the quickness with which Ridley Scott was able to replace Kevin Spacey with Christopher Plummer (a much more appropriate choice anyway) in the role of J. Paul Getty, All the Money in the World bears with it an overt statement about American values. That is to say, well, they’re not very good. But most of us have already been faced with that reality many times with each passing cultural and political landmark of recent years. Yet it’s nothing new. The only time we really seem to notice it, in fact, is when it’s pitted against European values–getting even more specific, Italian ones.

In David Scarpa’s third screenplay, adapted from John Pearson’s Painfully Rich: The Outrageous Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Heirs of J. Paul Getty, the emphasis upon the U.S.’ cultural divide with other countries is summed up in a line from one of J. Paul Getty III’s (Charlie Plummer) captors, Cinquanta (Romain Duris, a Frenchman for some reason playing a member of the ‘Ndràngheta): “I don’t understand you Americans. In Europe, family is everything.” This is, of course, in reference to the slow amount of time it’s taking for the Gettys to react to the threat on their kin’s life.

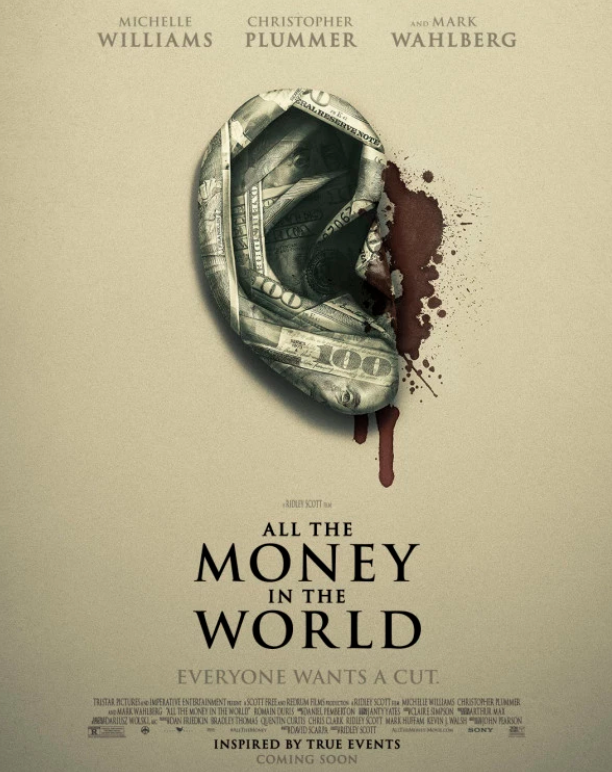

Beginning in Rome, 1973–a fraught time during which the militant leftist tendencies of the Brigate Rosse wrought fear and terror upon the nation–an innocent, lamb-like Getty III wanders the streets in the dark hours of the night, encountering prostitutes near the Palazzo Farnese who warn him that he should get home. As though tempting the fates, he insists demurely, “I can take care of myself.” This doesn’t seem to be the case immediately after when he approaches a VW van like a docile animal responding to his name. Plucked from the cobblestones and taken to the deep recesses of the Calabrian region, these mafiosi fully expect to get their cut (figuratively, and literally, as it later turns out). After all, as the tag line tartly puts it, “Everyone wants a cut.” And want it they do, especially from a man like J. Paul Getty, who is not only the richest man in the world at the time of the kidnapping, but also the richest man to have ever lived, all thanks to some sound investments in oil near Kuwait, of which one of his paid negotiators, Fletcher Chase (Mark Wahlberg), also a former CIA operative, helps sustain.

What he can’t sustain, however, is any level of compassion on the part of Getty, unmoved when his grandson’s mother, Abigail “Gail” Harris (Michelle Williams–who knew she’d be the most award-baiting of all the Dawson’s Creek alum?) calls to inform him of his grandson’s kidnapping. After she tells Cinquanta that she doesn’t have the seventeen million dollars they’re demanding, he balks and suggests, “Ask your father-in-law. He has all the money in the world.” Unfortunately, he lacks all the humanity in the world that it would apparently take for him to part with any of his fortune.

A flashback to Gail’s life while still married J. Paul Getty Jr. (Andrew Buchan) in San Francisco unearths the latter’s longtime struggles with both drug addiction and asking to reach out to his father for financial help of any kind. His absenteeism from his son’s life is perhaps what provokes within him a sudden touch of generosity in offering him a high-ranking position in Rome at Getty Oil Italiana after Jr. implores him for work at the encouragement of Gail, who has four mouths to feed.

J. Paul Getty takes a special shine to Paul when the family arrives in Rome, offering him a statuette of a minotaur that he claims to have purchased for eleven dollars at a market during his travels and is now valued at slightly over a million dollars. Paul takes the gift, and with it, a tour of Hadrian’s Villa, the place he tells Paul where he knew that this was the emperor he must have been in a past life, for it’s the only place on earth he’s ever felt at home. Not exactly a tender conversation, but it’s the tenderest J. Paul Getty can get.

In another flash to the past detailing the terms of the divorce, Gail’s lawyer insists that an intelligent woman like her’s only fault is in getting involved with “a degenerate” and an “imbriglione” (look it up) like Getty Jr., who has no problem losing track of his son while drugged out in Marrakesh. Naturally, Jr. himself isn’t there to deal with the terms of the divorce, but Getty Sr. and his lawyer, Oswald Hinge (Timothy Hutton), certainly are. To Getty Sr.’s surprise, Gail wants to no part of the money or the alimony, only the promise that she’ll retain custody of her children and that they’ll get child support. It is, in this way, that Gail is the only American in the film with any semblance of displaying an obligation to family. And to boot, an actual emotional connection (who knew it was possible?).

As Cinquanta states, “You’re born into a family and you remain obligated to it.” But a multibillion dollar fortune isn’t built upon obligation to anyone but the self. And Getty Sr. makes no attempt at masking his miserliness to the public with the notorious line, “I have fourteen other grandchildren, and if I pay one penny now, then I will have fourteen kidnapped grandchildren.” No, you certainly wouldn’t catch an Italian saying that–least of all an Italian mother. For there is no greater form of wealth to a European than la famiglia. Perhaps that’s why the continent has always been more prone to communism than North America, what with so little time to focus on capitalist ventures over concerns at home. Even so, a man can’t live on familial love alone, as is made clear by one of the leftists Getty III was consorting with before his kidnapping, declaring to Chase after he mocks, “I thought you were above money,” that, “Nobody is above money, but it’s in the wrong hands.” Then again, any excess amount of money can turn the “right hands” evil and corrupt. Just ask Karl Lagerfeld. Because worse than a burgeoning bank account causing one to lose sight of what’s important (like helping a family member in desperate need when one clearly has the means to do so), it also enables complete and utter cuntery without being checked. And not the fun kind that you used to enjoy while watching The Simple Life. As All the Money in the World underscores, there is no greater complication and compromisation of one’s morals than having money, a message that we somehow still need to be hit over the head with centuries after A Christmas Carol.