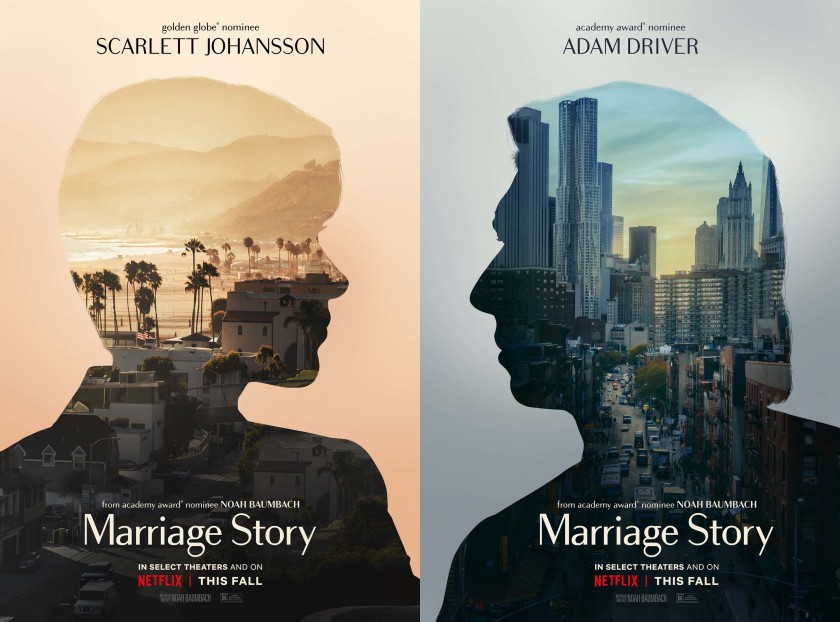

Carrie Bradshaw once asked, “If you love someone and you break up, where does the love go?” The answer, if you’re getting a divorce, seems to be that it simply gets absorbed along with the rest of your liquid assets into the court battle that will secure a legal recognition of the schism. In short, your love, property of The State, is legitimized and renounced by it when both moments come. Of course, this is a concept Noah Baumbach is all too familiar with, one he firmly established his mainstream career with when The Squid and the Whale became a critical darling of 2005 (though, of course, Baumbach had already been heralded in the independent film world in the 90s, ascending quickly–for it couldn’t have hurt to have film critic parents). While it is this film that focuses on his parents’ divorce and its effect on him as a child, he lends a new perspective to the genre by telling it through the lens of what he endured as an adult in his own divorce. Specifically to Jennifer Jason Leigh. Who, like Nicole Barber (Scarlett Johansson), files for divorce in Los Angeles despite the fact that her husband, Charlie Barber (Adam Driver), considers themselves “a New York family.”

That the two met in 2001 while she was starring in Proof on Broadway is a fact of his personal life also visibly present in his latest, Marriage Story, in which Charlie is a prominent theater director and Nicole “his” actress. Veering away from the “failure of the patriarch” concept present in his last movie for Netflix, The Meyerowitz Stories (evidently every movie of his needs to have “story” in it now), this one seeks to showcase a father who is “almost annoying” in terms of how much he loves being a dad. Thus, when Nicole flies to her hometown of L.A. with their only son, Henry (Azhy Robertson)–it bears noting that Baumbach and Leigh also had a son about Henry’s age when they divorced–assuring that she’ll be back once she finishes work on a television series, he’s taken by surprise when she sets up residency there. Moving in with her mother, Sandra (Julie Hagerty, forever young and hippie-dippy), enrolling Henry in school and throwing herself into her starring role for a non-theater medium for the first time in years (previously having abandoned L.A. for New York after a successful teen film made her an icon for flashing her tits [again, this smacks of Jennifer Jason Leigh]). As a result, their son quickly becomes Team L.A. as he drinks the Kool-Aid of all “the space” (mentioned sardonically throughout Baumbach’s screenplay as a grasping at straws selling point of L.A.) and sunshine.

This development couldn’t come at a worse time for Charlie, who has just taken his play (formerly starring Nicole) to Broadway and needs to have his head in the game in order to make it a success there. News of winning the MacArthur grant is also sullied upon his arrival in L.A. to visit Henry, at which time Nicole’s sister, Cassie (Merritt Wever), awkwardly serves him with divorce papers. Despite the fact that both Charlie and Nicole promised one another there would be no lawyers involved. But then, that’s how it always plays out–the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Nicole’s introductory meeting to her divorce lawyer, Nora (Laura Dern), is, in fact, one of the more unique scenes of the film, with Nicole relaying to Nora how she met Charlie without Baumbach relying on the usual cliche technique of a flashback sequence. Instead, Nicole recalls in a more soliloquy format how they met at a theater production posing as a party in someone’s apartment and that, the entire time, Nicole felt as though Charlie was playing all of his lines to her. As she suspected, she was right, and the two became inseparable from that night forward. In many respects, it smacks of the Marilyn Monroe/Arthur Miller dynamic, with Marilyn fleeing from Los Angeles at the height of her fame and dissatisfaction for the “tranquility” and “realness” of New York. Something Nora tacitly balks at Charlie for while they’re on the phone with one another, she in her quiet office with a serene view and he relegated to a honk-ridden street in the tourist-pocked Theater District. Yes, it’s not difficult for anyone to see why Nicole would want to return to her native West. Where one can breathe (though actually that’s not really recommended because of all the smog) again in ways both figurative and literal. And while Nicole might have found a new sense of “aliveness” in going to New York and falling in love with Charlie, she admits to Nora, “All the problems were there in the beginning… but I just went along with him and his life because it felt so damn good. In the beginning I was the actress, the star and that felt like something, you know, people came to see me at first, but the farther away I got from that, the more acclaim the theater company got and I had less and less weight. And he was the draw. I got smaller. I realized I didn’t ever come alive for myself. I was just feeding his aliveness.”

So it is that she is finally forced to reconcile that she can never live her own life without separating from Charlie’s. Even if a part of her will always love him. Indeed, a sequence at the outset of the film finds both parties explaining through voiceover what they like about the other person, a writing exercise we later find out was requested of them by their therapist, wanting to remind them that even though they’re separating, they ought to remember the reasons why they came together in the first place. While the comments are mostly favorable, Charlie offers one remark that cuts to the core of the worst elements about the so-called “evolved feminist Brooklyn guy”–something that Baumbach himself likely suffers from. Believing themselves to be endlessly “pro-female empowerment,” these men still revert to inherent stereotypes of how a woman ought to be, or at least act: the doting wife forever cooking and cleaning, offering a polished pussy to fuck when her husband wants it as well (a.k.a. when he is not cheating on her). Thus he passive aggressively notes, “And it’s not easy for her to put away a sock or close a cabinet or do a dish, but she tries for me.” This “off-handed” comment comes back to roost later in Marriage Story, when he seethes, “You’re a slob! I made the beds, closed cabinets!” So there it is–the fact of the matter being that modern men–especially the ones that wrestle with “modernity” most of all in New York–eventually still have to admit to themselves that what they want is not a “Katie girl” but a simple and conventional one. This is one of the more underpinning currents that drives the film as Nicole starts to discover who she is again (even if in the costume guises of David Bowie and Sgt. Pepper-ified John Lennon).

With a tension that builds to the crescendo of an evaluator (played with the best possible awkward perfection by Martha Kelly) coming to assess the dynamic between Henry and Charlie, the wrench Baumbach throws into his viewers’ divided loyalty is enough to convince a person to never get married. That the only value to it is ceaseless pain and struggle. For a compromise between two parties–especially when a snot-nosed kid is involved–is rarely if ever achievable.

Eventually, Nicole comes across as the more selfish party despite Charlie being vilified as such by her in the beginning. Yet it is the single gesture of her tying Charlie’s shoe (apparently her new signature after Jojo Rabbit) at the conclusion that proves she still has the sense of maternal humanity that men in a divorce often cannot.

The overall neo-Woody Allen flavor of Baumbach’s style (complete with the presence of Alan Alda and Wallace Shawn) reminds one of another fictional icon of New York (besides Carrie Bradshaw): Alvy Singer. Who declared in Annie Hall, “I don’t want to move to a city where the only cultural advantage is being able to make a right turn on a red light.” Charlie feels just the same. And maybe Baumbach, too. What they don’t seem to fathom, however, is that L.A. and New York have long been two sides of the same egocentric coin. Even if that coin is going straight to the divorce lawyer.