They say the true mark of wealth doesn’t begin until you can afford to start art collecting. One could argue, however, that Madonna unwittingly began her connoisseurship in the field when she struck up a romantic dalliance with then mere “street artist” Jean-Michel Basquiat. During the course of their relationship, Basquiat’s rise would briefly eclipse Madonna’s until 1984, when her performance of “Like A Virgin” at the inaugural MTV VMAs made her a household name.

It was Basquiat’s second show at West Hollywood’s Gagosian Gallery in early 1983 that prompted legendary art collector/gallerist Larry Gagosian to later recall of his first introduction to Madonna via Basquiat: “Everything was going along fine. Jean-Michel was making paintings, I was selling them, and we were having a lot of fun. But then one day Jean-Michel said, ‘My girlfriend is coming to stay with me.’ I was a little concerned–one too many eggs can spoil an omelet, you know? So I said, ‘Well, what’s she like?’ And he said, ‘Her name is Madonna and she’s going to be huge.’ I’ll never forget that he said that. So Madonna came out and stayed for a few months and we all got along like one big, happy family.”

Madonna’s understanding not only of the artistic temperament but what actually makes art “good” was founded during these early underground years spent among her fellow downtown aspirants, among them also Keith Haring and Futura 2000. It was her time spent amid the grit and grime, if you will, that ultimately fine-tuned her keen eye for making something “niche” palatable to the mainstream (see: “Vogue”).

But even before bringing ballroom drag to the Midwest, Madonna was infiltrating American homes with high art in the video for “Open Your Heart,” which, in addition to offering us pedophilia from an older female standpoint, also put a spotlight on the art of Tamara de Lempicka. With the famed Polish socialite’s art (specifically “Andromeda” and La Belle Rafaela”) repurposed as the art deco exterior of the “gentlemen’s club” Madonna works at, an audience that might never have seen or heard of a de Lempicka was exposed to the distinct cubist meets neoclassical style. While Madonna’s own oeuvre has been criticized for being lowbrow (certainly don’t get Morrissey started about it), “Open Your Heart” was the first strong indication of her curatorial skills having an elevated influence on modern pop culture, which, as of the 1980s, was sorely lacking in much substance (though not to say style, if Duran Duran’s and Flock of Seagulls’ aesthetic was any indication).

As Madonna’s artistry matured, so, too, did the content of her lyrics, with her fourth studio album, Like A Prayer, offering up feminist declarations of independence spurred by her divorce from Sean Penn most succinctly encapsulated by “Express Yourself,” the video for which did more than just cull from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, reinvigorate classic ideals of masculinity and make self-imposed bondage look appealing. What few realize, however, is that, in addition, the true source material for the David Fincher-directed video was not Metropolis, but a photograph from Lewis Hines’ series, called Men At Work, documenting the construction of the Empire State Building. The photo, captured in 1921, is called “Steamsfitter,” and depicts a muscular man wielding a giant wrench as he grapples with the machinery of a piston (it’s never not innuendo-laden when Madonna is involved). Cut to sixty-eight years later in 1989, when Madonna’s very specifically cast group of muscular, gleaming with sweat men are operating the same exact machinery with the same depicted gusto and burst of energy. That Madonna has never limited her net of reference merely to painting is a testament to her reverence for all mediums of art and the ability to incorporate them into her own compositions.

Photography would play another important role in one of Madonna’s next videos and most successful singles, “Vogue.” Mining from the canon of fashion photographer Horst P. Horst (who, fittingly, got his start as an assistant to Vogue photographer Baron George Hoyningen-Huene), Fincher and Madonna re-teamed to pay tribute to some of Horst’s most iconic photographs, namely Mainbocher Corset (1939), Lisa with Turban (1940) and Carmen Face Massage (1946). Alas, Horst saw it less as an homage and more as a ripoff, ultimately suing over the video’s final product. Elsewhere, Madonna once again showcased the de Lempickas from her private collection, “The Musician” and “Nana de Herrera” building on her other beloved-for-music-video-use pieces, “Andromeda” and “La Belle Rafaela.”

Reaching an oversexed point in her career when the criticism and condemnation (the zenith was during the combined release of Erotica and the Sex book) became so laughable that perhaps Madonna either thought, “Okay, I’m going to show you how intellectual I can be,” or maybe, more simply, “I just don’t give a fuck about appealing to the masses anymore,” the video for “Bedtime Story” exhibits Madonna’s position as a cognoscente of art at its most blatant. Released in 1995 and directed by Mark Romanek, the allusions to surrealist female artists abound. Reportedly, Romanek’s conceptualization for the video stemmed from his first run-in with Madonna, who was living in a hotel at the time while her home was being redecorated. To Romanek’s surprise, the only thing she had brought with her from the house to the hotel was one of the surrealist artworks she owned–though he never said which one. It was in this instant that he decided any video he might work on with her next would have to be one centered around surrealism. As Madonna would later note, the “‘Bedtime Story’ video was completely inspired by all the female surrealist painters like Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. There’s a little bit of Frida Kahlo in there, too.” Of course, Madonna’s love for Frida Kahlo is a separate commentary altogether.

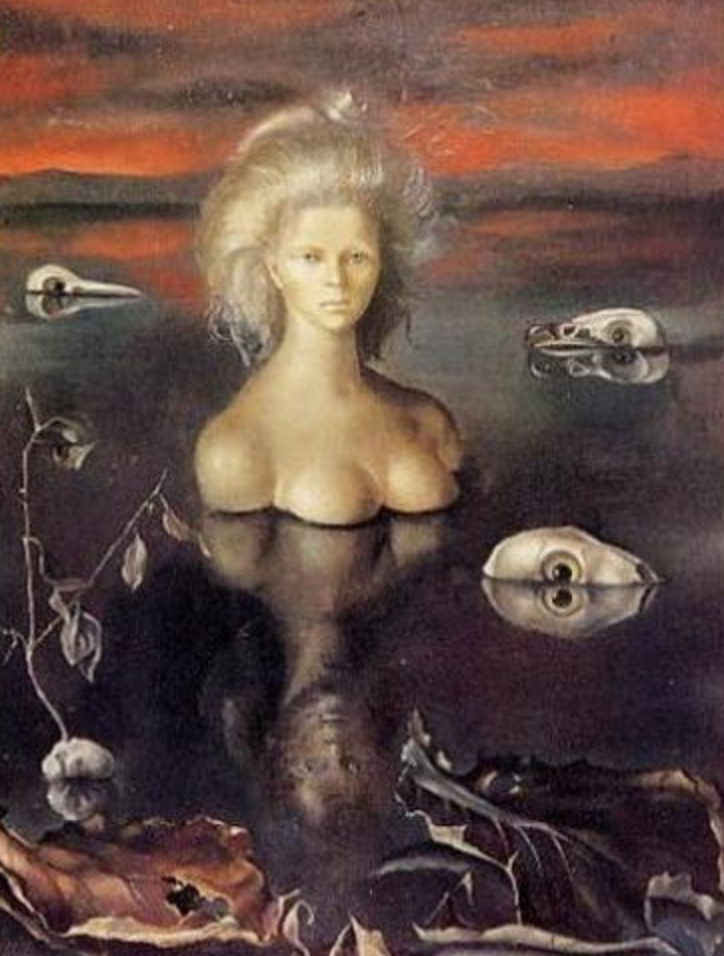

Remedios Varo’s most blatant influence on the video is in the scene of two underwater Madonna’s with heads framed in mirrors. The tableau is an almost (the “almost” part making it not plagiarism in a court of law) direct replica of Varo’s 1963 painting, “Los Amantes.” Appropriately, the other female artist heavily borrowed from in this video, Carrington, was a close friend of Varo, both of whom lived in Mexico at the same time as Kahlo. Carrington’s 1950 painting, “The Giantess,” serves as the direct inspiration behind the moment when a serene Madonna opens her nightgown-like dress to reveal a bevy of white doves emerging. The artistic parallels don’t stop there though. Madonna also wields the work of Argentinian Leonora Fini (Eva Peron isn’t the only Argentine rose she’s obsessed with, okay?). 1948’s “The Ends of the Earth” is dramatically employed for Madonna’s own immersion in water amid the skulls of various species. Even Fini’s later work is touched on with 1984’s “Vision Rojas,” a painting that depicts a girl in a white nightgown’s encounter with a levitating figure in red. The effect of Frida Kahlo can be felt most vividly when Madonna is depicted as having an eye for a mouth and two mouths for eyes, hinting at one of Kahlo’s most standout works, “Diego y yo.”

As a pool of water with the “Bedtime Story” lyric, “Words are useless, especially sentences,” crops up, one can’t help but also draw a comparison to renowned “word artist” Jenny Holzer. Considering Madonna’s known brand of irony, this seems a very premeditated touch to contrast against the affirmation that words are useless when Holzer only uses words as opposed to visuals to express herself.

And what would a Madonna experience be without a bit of the Freudian–literally? Apart from later in her life name checking Sigmund in “Die Another Day,” Madonna first chose to employ the painting of his grandson. Lucien Freud’s “Naked Man, Back View” is re-created to a tee with an overweight man draped in a red sheet instead of appearing fully nude (it had to be somewhat staid enough for MTV, after all).

But Madonna can never fully lend her expertise in art applicability to just one medium, also using Sergei Parajanov’s 1969 film The Color of Pomegranates–consistently polled as one of the greatest movies of all time–as an added flourish in the scene of a foot stepping on grapes against a ground with Arabic writing.

As one of the most expensive music videos ever made, “Bedtime Story” itself has been displayed in modern art museums like New York’s MoMA and London’s Museum of the Moving Image. That the art of others begat something itself so groundbreaking is a testament to how forceful painting and film can be when it speaks to and influences the right person–Madonna, obviously, being that person.

After one of the longest reprieves in between studio albums from 1994 to 1998, Madonna returned to recording after making the film and soundtrack for Evita and giving birth to her first child. The profound spiritual experience of both of these life events had Madonna going in a more ethereal route for the first single, “Frozen,” from Ray of Light. Returning to her love of photography and dance as she did for “Vogue,” “Frozen” is an overt love letter to Herta Moselsio’s 1937 series of Martha Graham in various modern dance poses, entitled “Martha Graham in Lamentation.” This selection as a means of expression in her own video is especially poignant when taking into account Madonna’s lifelong romance with dance, herself moving to New York City with the original intent of making it as a dancer–that is, until she was met with the epiphany that it’s not generally a very lucrative profession.

Still, she manages to incorporate her passion for the medium in almost every facet of her career. Directed by Chris Cunningham (also well-known for his work on Bjork’s–who incidentally wrote the lyrics to “Bedtime Story”–“All Is Full of Love”), “Frozen” framed Madonna in various poses of seeming entrapment in her own clothing in a similar monochromatic color scheme. Utilizing her body as the ultimate instrument of expression, the dance moves are enhanced by special effects (as abundant as they were in “Bedtime Story”) that find Madonna transforming into everything from a large black dog to a flock of black birds. Incidentally, it would not be the visuals that saw Madonna, once again, get sued in 2005 for plagiarism. Instead, it was Belgian composer Salvatore Acquaviva who would win the case against the star for borrowing a little too heavily from the melody from his 1993 composition “Ma Vie Fout L’camp (My Life’s Getting Nowhere).” Karmically speaking, perhaps Madonna got her comeuppance when Lady Gaga came out with “Born This Way” in 2011, markedly akin (“reductive” as Madonna notoriously called it) to “Express Yourself.”

Madonna’s next major genuflection to the art world would occur in 2003, with the video for “Hollywood.” Working once again with Jean-Baptiste Mondino, who helped her cause a scandal with 1990’s “Justify My Love,” “Hollywood” was a song that became most well-known for its VMA performance later that year, which infamously included a more publicized kiss with Britney Spears, even though Christina Aguilera was on the receiving end of Madonna’s lips as well. This is possibly why the video, with its esteem for French photographer Guy Bourdin, went slightly under the radar. That is, except to Samuel Bourdin, Guy’s son, who also brought a copyright lawsuit against Madonna for too closely replicating at least eleven images from the illustrious photographer’s catalogue, published primarily in the mid-1950s. Though the video also notably appropriated some of Madonna’s own work (more precisely an inverse scene that references “Erotica,” during which Madonna is hitchhiking with her clothes on instead of off), Samuel Bourdin didn’t find her use of his father’s art to be flattering, so much as a blatant violation. In a public statement he expressed, “It’s one thing to draw inspiration; it’s quite another to simply plagiarize the heart and soul of my father’s work.” And this is the thin line that Madonna has always dared to toe for the sake of reprocessing and regenerating art for a new audience. At the time of her peak, which some objectively deem the “Vogue”/Blond Ambition Tour era, she was funneling this knowledge of art to a youth culture that might never have willingly subjected themselves to it if not for their zeal for pop music and conical breasts (on that note: said seminal corset with conical breasts would itself become an art piece in the form of the traveling Jean-Paul Gaultier fashion exhibit throughout cities such as San Francisco and New York).

While her clout with the coveted twenty-five and under set has waned, even in her current incarnation–which includes many an esoteric Instagram post–Madonna remains committed to the cause of promoting art. To bring things somewhat full-circle, and apropos of her controversy-causing Instagram–Madonna recently put up a photo of herself in front of one of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s pieces at the Boom for Real exhibit at London’s Barbican Centre. Not one to lose out on the opportunity to play up the meta-ness of it all, Madonna also featured a video of her two adopted twins, Estere and Stella, running in front of a painting with the caption, “My past meets my present.” And in the present, there is still no more shrewd implementer of art into her music videos, stage shows and social media presence. If not for Madonna, there’s no denying a great many would be far more ignorant of culture, of “underground” works by artists who deserve to be known and more widely shared and appreciated.

In an interview with Aperture in 1998, Madonna declared, “Every video I’ve ever done has been inspired by some painting or some work of art.” Looking back at her vast arsenal of music videos (many of which would come after ‘98), it’s difficult to contest this statement. For even if one doesn’t see the artistic merit of Madonna herself, there can be no denying that her influence over what the culture at large chooses to absorb has made them more unwittingly erudite for it. For Madonna has never been merely a “pop star,” but an artist in her own right–and as such she’s keenly aware that to create new art, we must be aficionados of what’s come before us, perhaps subtly cognizant of the fact that even if no one knows what you’re talking about, they can at least give you the credit for coming up with it.