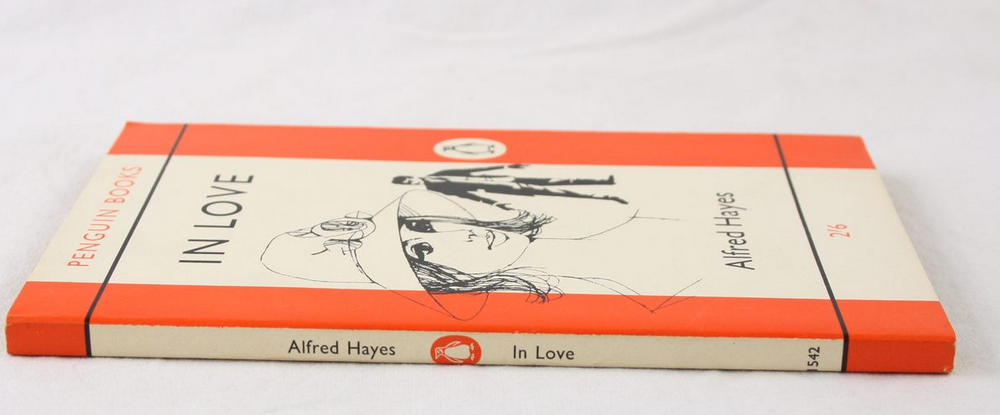

Alfred Hayes is one of those great writers that everyone should know about, but somehow tends to fall by the wayside when compared to other British titans like George Orwell. In addition to being known for his screenwriting during the height of Italian neorealism, Hayes was also the author of seven novels, including the masterpiece, In Love, published in 1953. His acute understanding of love from both the female and male perspective shines through in every sentence of this taut novel, showcasing the archetypes of man and woman by not even bothering to name his main characters.

…for nothing we want ever turns out quite the way we want it, love or ambition or children, and we go from disappointment to disappointment, from hope to denial, from expectation to surrender, as we grow older, thinking or coming to think that what was wrong was the wanting, so intense it hurt us, and believing or coming to believe that hope was our mistake and expectation our error, and that everything the more we want it the more difficult the having it seems to be…”

…by all the orthodoxy of kisses and desire, we were apparently in love; by all the signs, by all the jealousy, the possessiveness, the quick flush of passion, the need for each other, we were apparently in love. We looked as much like lovers as lovers can look; and if I insist now that somehow, somewhere a lie of a kind existed, a pretense of a kind, that somewhere within us our most violent protestations echoed a bit ironically, and that, full fathoms five, another motive lay for all we did and all we said, it may be only that like a woman after childbirth we can never restore for ourselves the reality of pain, it is impossible for us to believe that it was we who screamed so in the ward or clawed so at the bedsheets or such sweats were ever on our foreheads, and that too much feeling, finally, makes us experience a sensation of unreality as acute as never having felt at all.”

Regardless of not having any genuine sort of feeling for her at his core, the narrator is still hurt by the tendency of women to be the ones to leave first–to preemptively defend themselves from the emotional fallout. Our narrator notes, “Of course a woman always seems to choose, with a dismaying instinct, the god-damnedest of moments to end a love affair. Her dismissals always seem to come the way assassinations do, from the least expected quarter. There will be a note on the kitchen table, propped up against the sugar bowl, on exactly the day when most in love with her you arrive carrying a cellophaned orchid; or walking along the avenue, one arm about her waist, talking with great enthusiasm about a small house you saw for sale cheap thirty minutes from New York.” Again highlighting the general coldness of women, the ones who come across as the most love-obsessed, and yet, are the ones to go about it in the most clinical of fashions (e.g. what’s in his bank account?), the main character gives us a unique insight into the unexpected heartbreak of men.

I’ve always thought there’s nothing quite like the sight of a man at eight o’ clock in the morning, dressed in a business suit, and with his face shaved and his tie knotted and a brief case under his arm, having a quick coffee at an orange stand where already the frankfurters are glossily turning on a hot griddle. I’ve always thought there is no face quite like the face of a young girl, with her lipstick on and the exact pencilings of her eyebrows, coming up out of the subway and trying to make it to the office on time. I’ve always thought there is nothing sadder anyplace than seeing what people look like early in the morning as they go to work.”

I knew quite well why she was leaving me. I had always known. Nobody was necessary to me, she said. Not really necessary. I was fond enough of people and some I loved but none of them were necessary to me. She wanted to be somebody’s sun and moon and stars. She wanted them to die without her. She wanted them to need her always and forever… There was nothing she could ever really do for me but go to bed. It was the least of the things a woman wanted to do for a man. I would get tired of that and when I was tired there would be nothing else that she had to give me. I existed for myself. That was what frightened her. It was what always frightened a woman.”

…it’s the acrobat…with the dangerous, vanity-ridden, and meaningless life, who’s most like us. At least, so it seems to me: that paltry costume, that pride because the trick’s accomplished and once again he hasn’t fallen. The whole point is that nothing can save us but a good fall. It’s staying up there on the wire, balancing ourselves with that trivial parasol and being so pleased with terrifying an audience, that’s finishing us. Don’t you agree? A great fall, that’s what we need.”