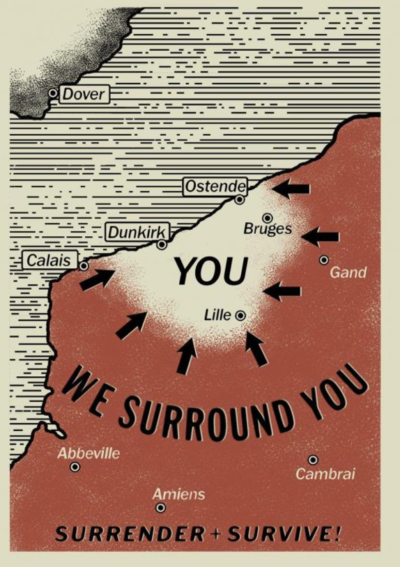

Like all requisite major Hollywood war movies that come about roughly every five to ten years, the deaths in Dunkirk set the stage of urgency within the first minute. No one is safe from getting picked off at random by a German soldier, and the ominous fluttering fliers that warn, “We surround you” don’t do much to reassure a Brit of his security. Tommy (Fionn Whitehead) is the only one among the group he scuttles through the town with to make it safely to the beach.

The Battle of Dunkirk–though the place sounds much prettier in French as Dunkerque–consisted of one of the most polarizing military and naval strategies in the Second World War, with British officers having to decide how many of Churchill’s projected 30,000 soldiers could feasibly be evacuated. Even the German general, Field Marshals, thought it might be best to avoid the Allied hot potato, anticipating a flare-up from their forces if it was aggravated too much like a hornet’s nest. Still early on (May 26-June 4, 1940), before the Americans felt the need to get involved, the Allied forces were comprised of the British and French (and yeah, technically the Polish, but no one ever seems to want to talk about them), who’ve always seemed to share a contentious rapport–“those fucking frogs,” etc. In fact, that’s one of the key plot points of Christopher Nolan’s disjointed narrative, told from the perspectives of land, sea and air, as the rescue gets underway. Tommy’s encounter with a seemingly mute soldier, Gibson (Aneurin Barnard), burying another allows for a fast friendship to be forged. When one is in the process of taking a shit and another is in the process of sand embalming, all veneers tend to go out the window. And this is where the rules of usual decorum fall away in war; too much is at stake to bother with the trivialities of politesse. Likewise, morality also becomes a concept that can easily melt away when spur of the moment decisions are being made in order to preserve one’s own hide. And yet, Dunkirk is a movie that doesn’t put a spotlight on the moral turpitude that can often fester and boil in the unique situation of war, so much as the inherent goodness that every man holds within his heart. Especially when it comes to rescuing other men. Just as sisters are doing it for themselves, so too, do men share a built-in code that ensures one goal: protect and save your own.

This is what drives the stoic, dutiful Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance), a civilian mariner enlisted by the Royal Navy to help bring back any soldiers they can. With his sons, Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney) and George (Barry Keoghan), Dawson takes to the sea, coming across a shell-shocked, hyper-sensitive soldier (Cillian Murphy) who has just been rendered the sole survivor of a U-boat attack. Assuming that the boat will take him back to England, the soldier goes into a frenzy when Dawson tells him they’re going all the way to Dunkirk to assist anyone they can. His psychological irascibility is, arguably, what makes him the least moral character of the film. Or at least the most defeatist.

Each character in Dunkirk, no matter how minuscule or briefly appearing, is forced to make a choice–one that is upright or self-serving. By and large, the choices made are upright, noble; the camaraderie revealed in this unprecedented evacuation offers the comforting thought that a crisis, at the very least, can bring out one’s humanity rather than suppress it. So maybe William Golding wasn’t totally right about people.

Then again, behind the scenes of the film itself, where was the mention of the black and Muslim soldiers integral to the evacuation, it’s been asked. Well, perhaps that’s a story for the next mandatory WWII movie Hollywood releases in the next five years. And as for its most obvious counterpart in terms of acclaim and similar historical value–Saving Private Ryan–Steven Spielberg might do the war genre a bit more justice, his film school 101 know-how at least giving more humanity to each soldier, telling us something of what he’s got waiting for him back at home–what’s truly at risk should he perish. One walks away from Dunkirk primarily remembering Harry Styles being a bit of a dick and Tom Hardy acting as only Tom Hardy could in the role of Farrier.