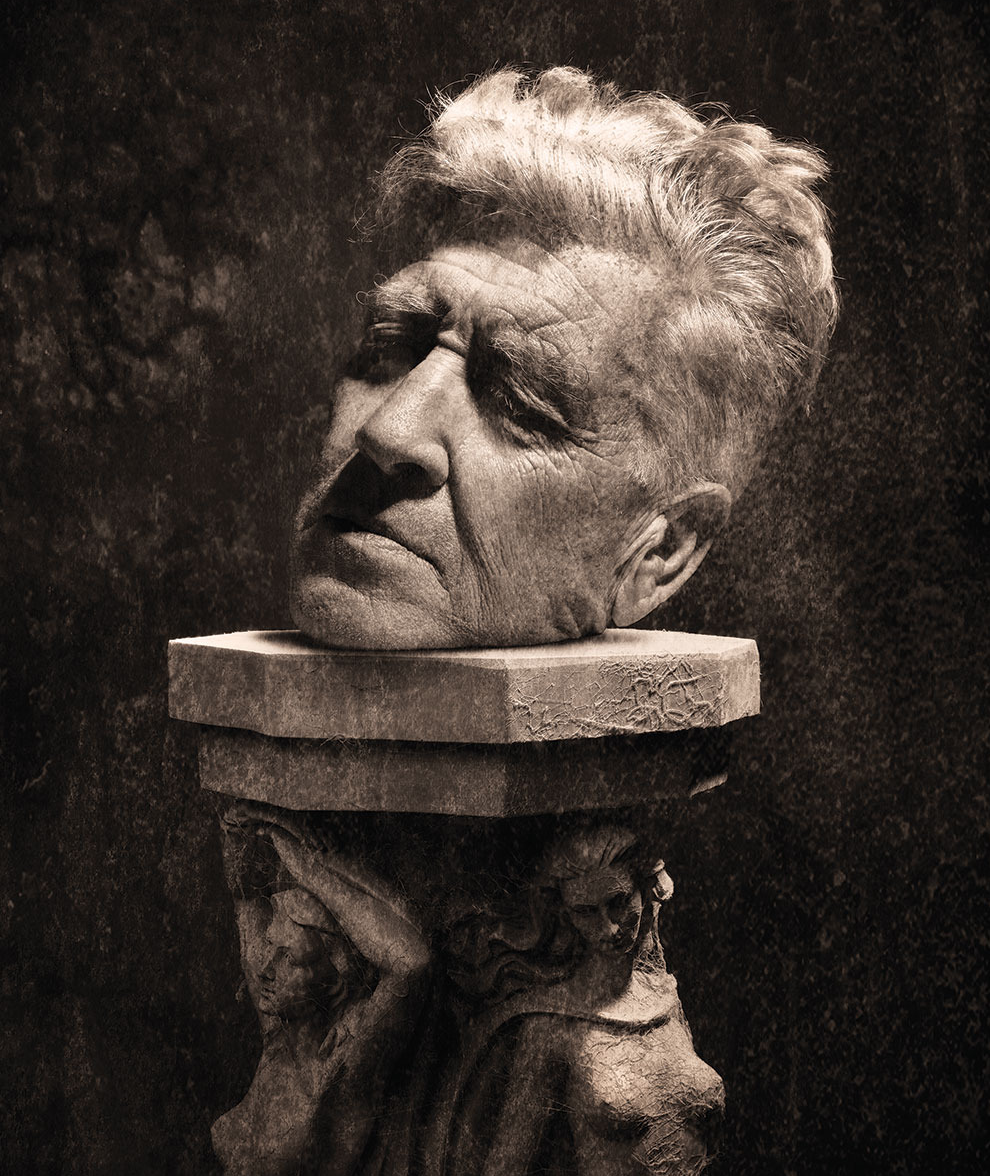

David Lynch, the king of conjuring interpretations and criticisms that will probably never signify any of what he originally intended (hence, some parties arguing that criticism is a totally inane field), has struck again by declaring, once and for all: “When you finish anything, people want to talk about it. And I think it’s almost like a crime.” So no, he doesn’t want to fucking discuss it and/or corroborate any of his fans’/audience’s theories about the “true meaning” behind his work, least of all the most dissected offering from his oeuvre, Twin Peaks.

At seventy-two years old, Lynch is also at an age where he especially does not give a fuck about pandering, a freeing phenomenon that happens to most old men, even if they never were known before for kowtowing to anyone in the first place. With the release of a new “memoir,” of sorts, Room to Dream, Lynch’s narrative approach is based on recollections and impressions of his life rather than any conventionally informed or analytical accounts of his past. And it wouldn’t be a Lynchian affair if there weren’t a bizarre twist, in this case, the fact that the book alternates between chapters as told from the perspectives of those who inhabited Lynch’s world at a certain point (e.g. Isabella Rossellini, his significant other until 1991, when according to Rossellini in the book, he cut off the relationship abruptly) and chapters re-creating those events from Lynch’s frame of mind. Co-authored by renowned journalist and interviewer Kristine McKenna, the formula was, essentially for McKenna to act as conventional biographer, with Lynch responding to each of her chapters with his own corrections and perceptions of what happened. It all lends a very Rashomon quality to the work, but then, the premise of Rashomon is Lynch’s bread and butter, speaks to the very arcane way he so seems to relish presenting the world in: that is to say, in an even more abstract and sinister form that engages and allures his legions of followers.

For good reason, thus, Lynch eschews explanations of his creations in any way, shape or form. For according to Lynch, “A film or a paining–each thing is its own sort of language and it’s not right to try to say the same thing in words. The words are not there. The language of film, cinema, is the language it was put into, and English language–it’s not going to translate. It’s going to lose.” So maybe that’s why, this time around, Lynch is using actual words to lend some insight into his rather ordinary and routine life (the man drinks coffee each morning, practices transcendental meditation and works–that’s his everyday). Nonetheless, he’s aware that the many crazed fans he’s attracted “will read the book for clues. But giving anybody clues has nothing to do with why I did it.” Instead, not to attempt to interpret Lynch–since he’s made it abundantly clear that he will never confirm nor deny your so-called incisive appraisals–the book’s release appears to have more to do with reverence for a medium that’s largely dead: film. Despite the fact that Lynch is more widely known for this one TV series, it is his incredible filmography–ranging from Blue Velvet to Mulholland Drive–that has left its indelible imprint on the recondite vernacular of cinema, and its offshoot, pop culture. And, try as he might, one cannot separate the work from the man, particularly when he makes statements like, “Happiness is not a new car; it’s the doing of the work. If you like the doing, the result will be a joy.”

Like an homage to the style of Hitchcock/Truffaut or Conversations With Wilder, the aim of Lynch’s first faintly expository biography reveals two things we already knew well enough about him: he loves the semiotic language of film and he is prepared to acknowledge mortality in a way that it takes people their entire lives to reconcile. The release of this book would appear to be part of that continued reconciliation. So no, he doesn’t need to explain his art to us. We’re just going to intuit from it what we will anyway, the same way he goes about creating his beloved work: by sheer feeling.